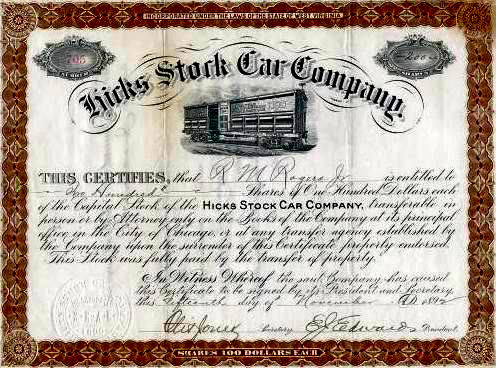

Hicks Stock Car CompanyHicks Humane Live Stock Car Company

The Hicks Stock Car Company was incorporated in West Virginia in 1890 for the stated purpose of manufacturing, operating and leasing cars of the patented type known as the Hicks Stock Car. The capital stock was nominally $5 million, only 12,500 shares of preferred having been issued and paid up in full, representing $1,25 million of capital on which no interest or dividend has been guaranteed. [Editorial comment: that sounds more like common stock than preferred.] Its President was E.J. Edwards and its Secretary was Otis Jones. {156} Edwards owned certain patents and a number of cars equipped with the patented appliances under the name of the Hicks Stock Car Company of Minnesota, which had been capitalized at $150,000. The stocks and patents controlled by Hicks (MN) were transferred by Edwards to R,M, Rogers, Jr., and then purchased by Hicks (WV) for $4.999 million of the capital stock of Hicks (WV), $1.25 million of which was preferred stock. [Editorial comment: is this the same $1.25 million mentioned above?] {156}

Presumably the company proceeded to buy cars and lease them to railroads for the transportation of live stock. We have seen evidence that suggests at least some arrangement with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe. {162} In May of 1893, the New York Stock exchange began a severe contraction. In June it crashed. The great Union Pacific, the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe, and other railroads were forced into bankruptcy. Car orders evaporated. Six car builders closed for the entire year. By the time the depression was over, 15,000 commercial firms, 600 banks and 74 railroads went down. The next few years would be a struggle to stay in business In late 1893, one Henry O'Hara of St. Louis—claiming to be the owner of 2,122 shares of preferred stock—applied to the Circuit Court in Chicago to have a Receiver appointed for Hicks, alleging the company had liabilities of about $2 million and less than $500,000 in assets. He told the court that he and several others had personally guaranteed a loan to Hicks from the Chemical National Bank for an extension of six months, and that Hicks had not repaid the loan, putting him at risk of having to make good on it. He also claimed to be a creditor of Hicks to the tune of $78,162 worth of cars he had furnished. He further claimed that E.J. Edwards, President of the company had, without the consent of the corporation or its stockholders, transferred to his father, John Edwards, 780 cars that were really the property of the company and that John Edwards had been drawing a monthly rental of about $8,000. {156} E.J. Edwards, President of the company, responded that the company was not insolvent, that O'Hara was “a St. Louis promoter” who had been given a contract to build 2,600 cars for which Hicks had paid all but $1,800 in preferred stock, and that at the present time the company owed O'Hara $10,000 against which it had a claim of $70,000 for non-fulfillment of the contract. {155} When the case was heard 13 January 1894, E.J. Edwards testified {157} that —

O'Hara’s application for a Receiver was denied. So in February 1894 he brought suit against the company for $120,000, alleging that during the year past he had sold the Hicks company 1,375 cattle cars and that there was a balance due on them of $80,000. Furthermore, he was owed dividends at 6% on his $315,000 of preferred stock. An interesting observation was made by the newspaper reporting this: “Neither the complainant [O'Hara] nor the defendant [Hicks Stock Car] is a manufacturer of cars, but is simply a dealer in rolling stock, acting between the manufacturers and the railroads and freight lines.” {158} We don't know what was the result of this suit, but we presume the judgment was in favor of Hicks, for it continued in business, and it was not likely to have done that if it had to come up with $120,000 in cash, and it is not likely O'Hara would have settled for payment in [more] preferred stock! In May, the Receiver for Chemical National Bank brought suit against John Edwards (the father of Hicks President E.J. Edwards) for $100,000, saying the Hicks Stock Car Company was indebted to it for $90,000 and that Edwards had signed notes guaranteeing repayment. {159} Again, we don’t know what was the result of this suit. But here the financial result would not have impacted the Hicks Stock Car Company. In January 1895, a resident of West Virginia, one Royal J. Whitney applied to the U.S. Circuit Court to have a Receiver appointed for Hicks, alleging, among other things that —

Whitney also asked that the company be restrained from disposing of any other of its effects, that an accounting be made, and that the fraudulent transactions be set aside. {160} A restraining order was issued until a final hearing could be held. But by the end of the month, the Railroad Equipment Company of New Jersey had filed a bill in the U.S. Circuit Court to foreclose against the Hicks Stock Car Company on a leasehold in the amount of $1,651,400 secured by 2,800 cars operated by the Hicks company. The cars had been purchased two years earlier and were to be paid for at the rate of $17,250 a month. Railway Equipment alleged Hicks had missed the last two monthly payments. {161} The Hicks Company’s day in court came 6 February. A total of three applications for Receivership were heard —

Whitney requested that the two latter entities be restrained from foreclosing their leases. {163} The company, for its part, requested the appointment of Henry A.V. Post and Thomas Carmichael of New York, the guarantors of the lease warrants to the banks of New York holding them. The judge declined the company’s request with the comment, “O, no. . . I can not appoint the receivers from New York; that would not leave anything in this court but the bill itself. You have got to suggest a Chicago man, whom the court can find when it wants him.” {163} Nevertheless, a few days later, the judge did appoint Post and Carmichael receivers for the Hicks Stock Car Company. But the receivership was to apply only to the rolling stock of the company. On the general receivership of the company, the judge deferred to the application for receivership filed in West Virginia by Royal J. Whitney. The financial reporter for the Chicago Tribune said, “The double receivership means the death of the Hicks company.” He also said, “The company was capitalized at $5,000,000—all with the exception of $500,000 being water!” {164} It would be interesting to know just what transpired in the West Virginia court and during the receivership of the Hicks Stock Car Company. But at this time we have no idea. If you know anything, please contact us. The only other report we have concerning Hicks is a financial announcement in the New York Times for 1 June 1900, announcing that “Thomas Carmichael, William Nelson Cromwell and E.W. Clark, Jr., have been appointed as a Reorganization Committee by a majority of holders of the Canda Cattle Car Company, Consolidated Cattle Car Company, and Hicks Stock Car Company Trust obligations, and Railway Equipment Company bonds issued in connection therewith. Holders of such securities can become parties to the reorganization agreement by depositing their securities with the First National Bank of New York on or before June 30.” According to one authority {165}, “Hicks was taken over by J.W. Street’s Western Stable Car Line in 1902.” Henry Clinton Hicks of Minneapolis, Minnesota, had at least six patents on stock cars to his credit. He may have had more, but the way the U.S. Patent Office classifies them, we can never be sure we have found all of them. The six we have found are —

But none of these patents provide for a car like the one pictured above. On the other hand, Bohn Chapin Hicks, also of Minneapolis, Minnesota, had at least 17 patents on stock cars to his credit, all but the first two assigned to the Hicks Stock Car Company of West Virginia. The 17 we have found are —

|