Wason Mfg. Co. - Page 2

About 1867, Wason purchased the extensive property of the failed Springfield Car

& Engine Company, or at least whatever was left of it. This covered nearly four

acres near the passenger depot at Springfield, and included —

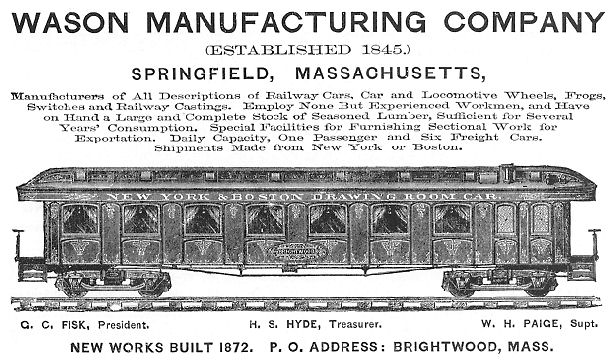

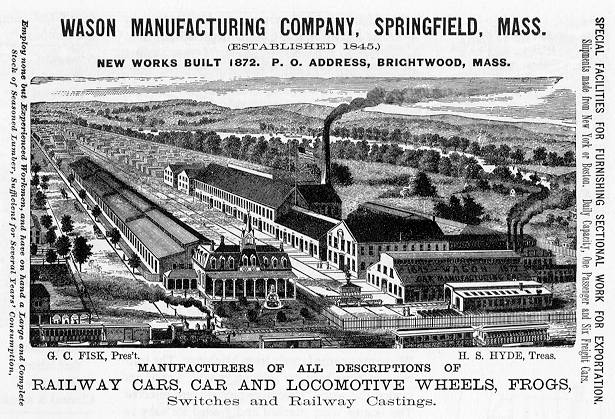

About 300 men were employed in these works, with a monthly payroll of $10-12,000. They were estimated to consumed 1,000 tons of cast iron, 450 tons of bar-iron, 30,000 pounds of brass and composition castings, 450 tons of coal, and a million feet of lumber annually, doing business valued at more than $500,000 per year. The foundry, described above as “still owned separate and apart from the car works” had been purchased in 1851 by Thomas Wason, S.W. Ladd and G.W. Lawrence, under the name of Wason, Ladd & Company, to manufacture car wheels and other railway castings, both for the Wason works and for other railroad companies. {402} In 1868 the Boston & Maine Railroad introduced two compartment-style drawing-room cars built by Wason. These were 45' long and divided into six staterooms, each with accommodations for seven. They were outfitted in lavish style with walnut and cedar paneling and had hot water heating. In 1869, Wason built 75 passenger cars for the Central Pacific Railroad, and 2,600 freight cars, the total amounting to $1.7 million {457} (equivalent to something over $20 million today). When the news of the completion of the transcontinental railroad was received in Springfield, the workmen of the Wason factory paraded through the streets carrying the tools of their trade and numerous banners, at least one of which said, “Our cars unite the Atlantic and Pacific.” {458} One of these cars is preserved at the 1897 Railtown State Park in Jamestown, California. According to information received from a gentleman documenting it, it was #43 of the Wason order and arrived in August of 1869. The 1st two of its sister cars were delivered to Governor Stanford at Promontory when the transcontinental railroad was completed and returned to Sacramento with him. Wason cars truly were the 1st to make the transcontinental trip! As the advertisement below shows, Wason railroad cars were used all over the world, with exports making up over half of Wason’s business. Its posh private cars were bought by wealthy industrialists, political leaders, and nobility. By the time of Thomas Wason’s death in 1870, the Wason Manufacturing Company had become a major car builder, and Springfield’s largest industry. The original works on Lyman Street that were not large enough to completely house a single car had grown to a large brick manufactory. {457} At Thomas Wason’s death, George C. Fisk, Wason’s one-time bookkeeper, part owner since 1853, and currently treasurer of the corporation, became its president. {457} Under Fisk, the Wason company built a huge new plant at Brightwood, slightly north of Springfield, a tiny town that drew its name from the estate of Dr. J.G. Holland, which later became Fisk’s home. The new location consisted of 16 acres bounded by Plainfield and Fairfield Streets, and Birnie and Wason Avenues. With the Wason works now located there, the little town soon became a flourishing village. {457} A source writing about 1884 says this plant included — {457}

The new Wason plant was considered a “model” operation. Its centerpiece was the transfer table that ran from one end of the manufactory complex to the other. 45'-0" wide and weighing 9 tons, it ran on a track 1,000' long. It had a vertical boiler and 12 horsepower engine that reeled itself along a stationary chain. It could go from end-to-end in just two minutes. {7}

But Wason’s future was not to be all bright: in 1873 prosperity came crashing down for everyone. In September the bottom fell out of the stock market. By the end of the year, 5,000 businesses failed. 89 railroads defaulted on their bonds, and railroad building stopped cold. Railroad-related businesses such as Wason came to a grinding halt. It would be six to seven years before things got back to normal. We have found no accounts of how Wason weathered these times, but it obviously did. As King was preparing his Handbook of Springfield in 1883, George C. Fisk was president of the company, while Henry S. Hyde was its treasurer and a principle stockholder. Lewis C. Hyde was the secretary of the company, and Henry Pearsons was superintendent of the works. {464} By 1883, business was back to “normal,” and even better. The economy had expanded extravagantly—too extravagantly. And in 1884, the collapse of the banking house of Grant & Ward brought it all down again, but this time it did not last nearly so long. By the 1890s Wason was turning out $1.2 million worth of railroad equipment each year. One year this consisted of fifty steam locomotives (?), 450 rail cars, more than 100 trolley cars, and 50 railroad snow plows. {6} [Interesting: we have found nothing anywhere else that indicated Wason built locomotives.] And it appears that Wason had largely dropped out of steam railroad car building by 1900, concentrating on trolleys and electrified rail cars, for which the company built all the parts except for motors. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||