Harrisburg Car Mfg. Co. - Page 2

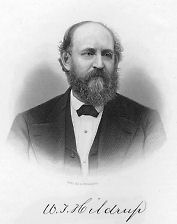

General Manager Hildrup went to the stockholders and told them they must come up with $110,000 immediately or lose their investment entirely. Our source does not say whether they did or not, but one must suppose they did, because the company did not go under. During 1875 Harrisburg laid off employees and took to issuing script [I.O.U.’s] to keep up what operations it could. During much of the year the works stood idle. The company lost money for the first time in its history. In 1876, as the depression began to ease slightly, production amounted to $306,500 (compared to $1,586,000 in 1873). There were no profits, and hence no dividends. In 1877, as the depression eased even more, Harrisburg was able to obtain operating funds, but car orders were at a minimum. In 1878, things began to look up. Confident that good times were on the way and the cost of materials would rise, Harrisburg began to sign long-term contract for materials of all sorts. Car orders increased and even the foundry and machine works were put to work building cars. Cheap materials and rising product prices proved—as always—a formula for success, and the year ended with a profit.

In 1880, production advanced to 12 eight-wheeled box cars daily and held steady at that level. In 1881 Harrisburg Car Works produced 3,402 cars, and at the end of the year had orders for 2,630 more. That year it grossed almost $2 million, and in 1882 it grossed well above $2 million (equivalent to almost $36 million today). {60} But prosperity lasted just 4 years. The collapse of the investment banking firm of Grant & Ward in 1884 took down 15 other financial firms and again made it hard for industry to raise capital. Car orders plummeted. A company history puts it succinctly: “Business was terrible in 1895.” And it would improve only slowly. By the mid-1880s, the railroad building boom had reached its peak. The lines were over-supplied with rolling-stock. Competition would become the name of the game. Recovery would be slow for not only Harrisburg, but for all car builders. By the end of the 1880s, meat packers had perfected the art of preserving beef. What was needed was a new kind of transportation: a refrigerated box car. Harrisburg was the first to build them. Things looked up, and the works was enlarged, based on the expectation of more orders. Yet all was not well. The financial difficulties of the 1880s had left the company with little in assets other than outstanding orders for roughly $1.2 million worth of cars. In 1893, the failure of Baring Brothers, a London dealer in American railroad securities, once again put a pinch on capital expenditures by the railroads. Many orders for new cars were cancelled, and where new cars were delivered, payment was defaulted. Despite Hildrup’s best efforts, the company was soon in bankruptcy court, never to emerge. Epilog —Soon refrigerated cars were coming back to the non-existent Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company for repairs. Pipes leaked and spoiled the freight. William Hildrup’s son, William T. Junior, had been trained as a mechanical engineer at the University of Pennsylvania. Upon his graduation in 1883, his father had employed him as his personal assistant, so he could learn the management of the business. Young Hildrup had brought in two former classmates, David E. Tracy and J. Hervey Patton. With the demise of the Car Company, none had jobs. But somehow they managed to raise $100 each and formed the Harrisburg Pipe & Pipe Bending Company, Ltd. (a British corporation, in order to avoid involvement in the Harrisburg bankruptcy). Young Hildrup devised a way to repair the bends in the pipes that were splitting due to the poor quality of the pipe, and soon a new industry was born: an industry that would grow and expand, in 1935 becoming the Harrisburg Steel Corporation and in 1956 becoming HARSCO. But that's another story ... You can visit their website at http://www.harsco.com Cast of Characters —

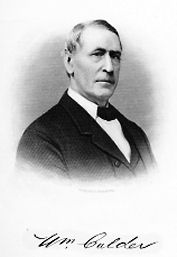

In 1857, Calder undertook the completion of the Lebanon Valley railroad, and in 1858 became a member of the banking firm of Cameron, Calder, Eby & Co., which later became the First National Bank of Harrisburg. During the Civil War he supplied the government with no less than 42,000 mules. He was also involved in the founding of several other businesses in Harrisburg. David Fleming (1812-1890) attended the Harrisburg Academy (high school) and at age 17 became a teacher of higher mathematics. Due to ill health, he pursued a career in business, becoming a clerk for a contractor on the Baltimore & Port Deposit railroad. After awhile he was put in charge of shipping pine timber for the Navy yard at Washington, D. C., from North Carolina. In 1838 Fleming returned to Harrisburg and for several years edited a local newspaper and reported legislative proceedings to other newspapers. He also studied law, and was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1841. He practiced law until his death, while at the same time being involved both in politics and with numerous business interests. In 1847 he was elected Chief Clerk of the state House of Representatives. In 1854 he was elected District Attorney and served in that position for three years, declining to run for re-election. In 1863 he was elected to the state Senate Fleming was one of the founders of the Harrisburg Car Works in 1853, subsequently obtained its charter, and succeeded William Calder upon his death, in 1880, as president and also a member of the board and stockholder of the Foundry and Machine Company, which originated from the same enterprise. Jacob M. Haldeman [Halderman?] (1781-1856) had built up an iron making business across the Susquehanna River in Cumberland County with money borrowed from his father. He expanded his operation with rolling and slitting mills, and supplied iron to the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry during the War of 1812. He was one of the organizers of the Harrisburg Bridge Company, and provided financial support to the bridging of the River. Putting his profits from iron making into land, he bought up local farms during an economic downturn, and in 1830 moved to Harrisburg. He was actively involved with a number of local enterprises, serving as president and longtime director of the Harrisburg Bank, holding the same positions with the Harrisburg Bridge Company. He also invested in the newly-formed Dauphin Deposit Bank and the Harrisburg Cotton Mill.

In 1852 he set up shop on his own at Elmira, New York, but before he could get into production, he was offered the position of General Manager of the new Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company. He literally nursed that enterprise through good times and bad until it could go on no longer. He outlived it by less than nine years. For More Information —Eggert, Gerald G. Harrisburg Industrializes; The Coming of Factories to an American Community. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

Hildrup, William T. History and Organization of the Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company. Publisher unknown,1884.

|