Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company

William Calder Jr., who in 1851 became manager of the stage line founded by his father, is credited with bringing the idea to fruition. In 1853, he brought together Fleming, Jacob Haldeman, Augustus Heister (an associate County Judge), William Murray (a lumber merchant), Elias Kinzer, Thomas Wilson (a machinist), and Isaac G. McKinley (the newspaper editor). Together with himself, they formed a joint stock co-partnership with working capital of $25,000 (equivalent to roughly a half-million dollars today). Calder also secured the land on which to build the car works. William T. Hildrup, an experienced car builder who had just started up his own car business at Elmira, New York, was brought in to provide the technical know-how. And thus was born the Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company. Hildrup, named General Manager of the company, saw to the construction of the works, quickly erecting a foundry, planing mill, machine shop and erecting shops in a “U” shape with the opening in the middle used for the storage of lumber. He acquired the necessary machinery, and he hired men to operate it. But then he had to train the men, for Harrisburg had no industry from which to draw experienced workers. During the early years, this was nearly a full-time job.

Eggert {59} describes a report in the Harrisburg Morning Herald of 19 May 1855 that said (in his words):

The works had hardly more than gotten off the ground when it was hit by the financial panic of 1857. Orders for railroad cars dried up, completed cars were rejected by buyers that could not pay, and the firm was quickly deep in debt. The partners, much more involved in the lives of their employees than in a typical industrialized city of the time (which Harrisburg was not), and no doubt not wanting to lose the skilled laborers they had so assiduously educated and trained, found other work to employ their men. Among other things, bridges, station buildings and a freight house were built for regional railroads. Work was done on the Pennsylvania Canal. Farm implements were manufactured. One way and another, the company—and the community—survived. By 1859, things were more-or-less back to normal. But they stayed that way only two years. 1861 brought the outbreak of the Civil War, and again business took a nosedive. But it very shortly picked up and even boomed, for Harrisburg—as a strategically located rail center—became, in Eggert’s {57} words, “one of the nation’s busiest centers for amassing troops and supplies and forwarding them to the eastern front.” All the partners made money in one way or another, supplying the needs of the Union Army. The effect on the car works was primarily one of maintaining its work force. Each call for recruits would result in the older, more experienced men leaving for the war front. Inexperienced younger men had to be trained: generally, just in time to be recruited at the next call. This situation was made even worse shortly after the battle of Gettysburg (3 July 1863, and less than 40 miles away), when the first draft was instituted. Though prepared to provide army wagons, gun carriages, cannon balls, bomb shells and various other munitions, it appears that the only contribution to the war made directly by the Harrisburg Car Works other than building rolling stock was the manufacture of army wagons, of which they built some 400. During the war (1863) the original partnership was dissolved and the company was reorganized and incorporated. Two of the original nine partners had died and two others had sold out to the remaining partners. The firm had paid only one dividend in its nine years of existence; all other profits having gone into plant and equipment. Except for single shares sold to three other men to meet the legal requirements of incorporation, three of the original partners acquired all the stock of the new corporation: William Calder, its President, W.T. Hildrup, its General Manager and Secretary, and David Fleming. It was capitalized at $75,000. The Harrisburg Car Works expanded rapidly, and capital was increased to $300,000 in anticipation of a building boom after the war. But instead of the expected boom there came a slump. Many railroads decided to build their own cars and save the profits they saw going to the car builders. Harrisburg put much of its resources into the building of machine tools. The railroads soon discovered that they could buy cars cheaper than they could build them, and business once again boomed for Harrisburg. But the casualty of the slump was the manufacture of passenger cars. After the war, Harrisburg built nothing but freight cars. One factor contributing to Harrisburg’s resurgence was the Pennsylvania oil boom. Oil had been discovered at Titusville in 1859, and by 1865 Pennsylvania was in the midst of an oil boom. Tank cars were in great demand, and Harrisburg was ready to supply them. Harrisburg’s early tank cars were nothing more than a conventional flat car with a metal tank sitting on top stabilized by wood blocks. An iron railing around the perimeter of the car was supported by wood stanchions. The design was improved and modernized during the following years, but always retained the wooden frame.

But the prosperity of the car business cramped the style of the machine tool business. So the company purchased 20 acres adjacent to its works into which it could expand. Then in 1869, there was a rumor the Pennsylvania Railroad might be interested in buying Harrisburg. Figuring that what the railroad really wanted was the land, Harrisburg bought even more. But the rumor proved untrue. “Stuck” with the extra land, the company moved the machine tool operation onto the new property, and was soon profiting greatly from that operation as well. Soon it was incorporated as the Harrisburg Foundry & Machine Company, capitalized at $200,000. An unidentified newspaper of the time reported on 25 April 1872 that “a very spectacular fire (had) destroyed the huge sprawling plant of the Harrisburg Car Works at Ninth & Herr Streets with a loss of $600,000.” Insurance covered the bulk of the loss, and legend has it that Hildrup sketched up plans for a new works that very night and put his men to work building a new plant the next day even as the ashes were cooling. A company history of the Harrisburg Steel Corporation says that the rebuilding took six months to the day: May 1 through July 1, 1872. On the opening day 12 eight-wheeled cars were produced. General Manager Hildrup reportedly gave his men a week’s vacation, and himself departed on a trip, only to be greeted on arrival by a telegram saying the new “fireproof” machine shop and foundry buildings had just burned down. He returned immediately and had them rebuilt in less than two weeks. The rebuilt works had a total of 19 “fireproof” buildings—mostly of brick—with pipes, fireplugs and hoses throughout for fire fighting, and its own volunteer fire company.

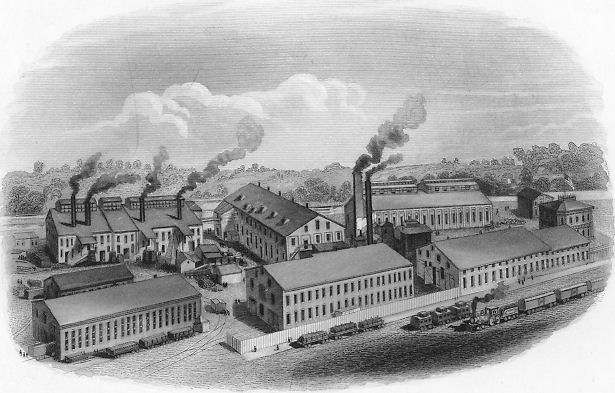

Eggert {58} gives the following statistics for the rebuilt works:

Continued. . . |