New England Car CompanyNew England Car Spring Company

|

| Were there two New England Car Company(s)? Or just one with quite a long life and virtually no mention in either press or trade press? The first article below is our original one. The second is the result of a tip from a correspondent. |

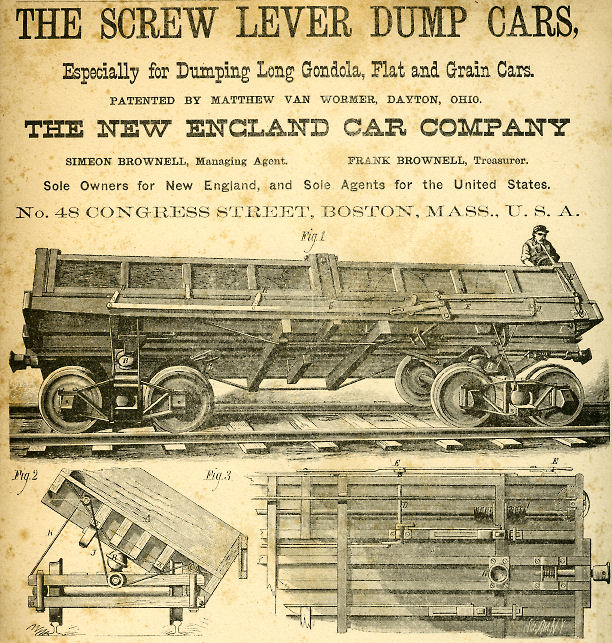

The New England Car Company appears to have been organized about 1879/80 for

the purpose of promoting an 8-wheeled “tip car” (as the type is described in

the 1888 edition of The Car-Builders’ Dictionary) designed by

Matthew Van

Wormer.

We don’t know yet exactly when it was established [but see below], but we do know it was either a corporation or a joint-stock company, {338} with Simeon Brownell as President and his son Frank Brownell (1856-??) as Secretary-Treasurer. Offices were early established at 48 Congress Street in Boston.

|

Click pic for more readable size. (Source unknown) |

The Boston Daily Globe for 13 March 1881 says —

“The New England Car Company is meeting with success in introducing its improved screw lever dump car. The most prominent railroad superintendents and master car builders in New England indorse it in unqualified terms. The company has closed contracts and introduced it on six well-known New England railroads, and is negotiating with several others. The company claims that one man could dump a car containing twelve or fifteen tons inside of three minutes. The cars are now in practical use, and it is being shown every day that one man can dump a load of eighteen to twenty tons and right the car up in less than two minutes, thus saving a vast amount of labor, as the company claimed. Several wholesale coal dealers have closely examined and practically tested the car, and warmly indorse its merits.”

An advertisement to sell shares of the New England Car Company stock {338} quotes a letter of endorsement from W.H. Paige, Superintendent of the Wason Manufacturing Company, saying —

|

“Having recently built three of said cars, and thoroughly tested same with 18 tons coal, one man at the lever dumped the car and righted it up in less than two minutes. Therefore I fully indurse same, and believe said car will be adopted and used on all railroads in the country.” |

It appears that Wason was the builder of at least the first few cars, {339} and we have found no evidence that the New England Car Company ever built its own cars. It is quite possible that it was purely a front-office company with someone else actually building the cars.

It appears that almost before the ink was dry on the newspapers, the company either —

| 1. | changed its name, |

| 2. | was reorganized, or |

| 3. | spawned a 2nd entity. |

Any of the three possibilities could be true. Note that the earlier advertisement (above) says, presumably about the Van Wormer patents —

“Sole Owners for New England, and Sole Agents for the United States.”

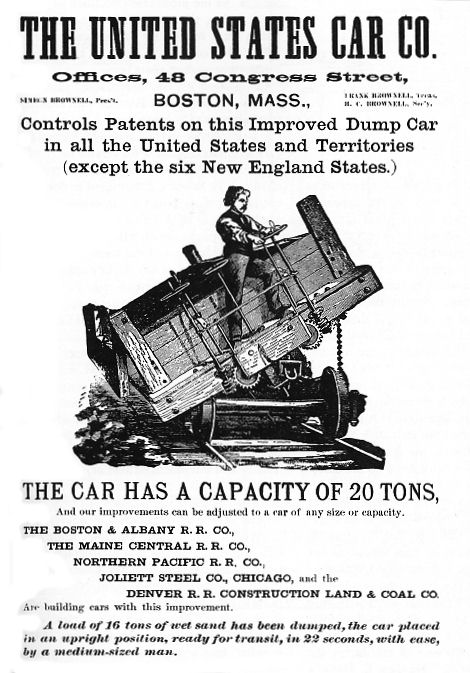

The later advertisement (below) says —

“Controls Patents on this Improved Dump Car in all the United States and Territories (except the six New England States.)”

The new company still controlled the patents outside New England (that is what “Sole Agents means”), but it has lost the very thing it originally claimed to own: its interests in New England.

|

Click pic for more readable size. (1881 Edition, Poor’s Manual of Railroads) |

Simeon Brownell was President of the new company, and his son Frank was still Treasurer, but the position of Secretary was now held by Simeon’s youngest son Harry C. Brownell (1859-??).

We have no idea yet what became of either company. It is possible they continued to exist parallel to each other, one representing the patents in New England, and the other outside New England. We have only a few further bits of information —

| 1. | Matthew Van Wormer filed for, and was granted, two additional patents after 1881 (see table below). |

| 2. | Simeon Brownell’s sons Harry and Frank witnessed the earlier of these, filed in April 1883. |

| 3. | Matthew Van Wormer moved to the Boston area (Melrose) sometime after he made application for his 1881 patent and before he made application for his 1883 patent. |

| 4. | Matthew’s son Clemson L. Van Wormer filed for a patent on additional improvements to the dump car in 1884 and it was granted in 1885. |

| 5. | Clemson’s application was witnessed by Matthew Van Wormer. (His father?) |

| 6. | At the time of the 1900 census, Simeon Brownell’s son Charles was living at Andover, Massachusetts, and gave his occupation as “Car builder.” |

We can speculate as to what happened, but would appreciate any information you might contribute. If you have any insights, or knowledge, or disagree with our speculation, please contact us, especially if you can locate any of these principles in any census after 1880.

Our speculation is that businessman Matthew Van Wormer had put up most of the money for the New England Car Company, and when he saw the profits attending the fruits of his inventions, he moved to the Boston area and took control of the company. The Brownells took their agency agreement for sales outside New England and began a new company called the United States Car Company. Neither company was successful in obtaining substantial contracts, and if either lasted until 1884, it was taken down in the May 1884 stock market collapse and ensuing depression.

The Car —

Van Wormer’s dump car was not the first railroad car designed to tip sideways to dump out its load. But it may have been the first 8-wheeled car to do so. Early side-dump cars were of the 4-wheeled variety, a much simpler base from which to work.

Van Wormer’s car appeared little different from any ordinary gondola car of its day: one that required the load to be shoveled out of the car with great expenditure of labor. But Van Wormer’s car was different in a great many ways. (In reading the following description, it may be helpful to refer back to the illustration heading this article. We have also provided hot-links to our version of the Railway Car-Builder’s Dictionary.)

| 1. | Where an ordinary gondola car has a body bolster with a center-pin protruding rigidly straight down to provide a pivot point for the truck, Van Wormer’s car had a body bolster that contained the seat of a ball joint, and the head of the center-pin was a ball around which the seat revolved. This allowed the body of the car to tip to the side as much as 45 degrees. |

| 2. | To keep the car level, Van Wormer’s car had side bearings on both truck bolster and body bolster in a fashion similar to that of conventional cars. But on Van Wormer’s car the body side bearings were attached to levers that could move those on one side or the other out of the way so that the car body could tip in the desired direction. |

| 3. | To control the tip, and provide force if necessary, a workman rotated a hand-wheel mounted on the end of the car similar to a brake wheel. A worm gear attached to the bottom of this shaft engaged a gear on the end of a shaft that ran the length of the car body. Two drums mounted on this shaft engaged two chains, each of which was attached to the outer edge of one of the truck bolsters, ran up and around the drum, then down to a sheave mounted at the center of the truck bolster, then up and around the drum on a corresponding shaft on the other side of the car body, and thence to an attachment at the other outer end of the same truck bolster. (See fig. 2, above.) When the horizontal shaft was rotated, the chain pulled the car body down on one side and allowed it to rise on the other. By turning the wheel in one direction, the car was tipped to one side. By turning the wheel in the opposite direction, it was tipped to the other side. Of course, it could be tipped only toward the side from which the truck side bearing had been moved. [Note that the workman tipped as the car body tipped. Bet he really had to hang on tight as the car body neared 45 degrees!!] |

| 4. | The side planks of the car, rather than being supported by stakes as on an ordinary gondola car, were divided into sections supported by a framework that allowed them to pivot outward from the top. They were held closed by a system of levers that could be released by the workman at the end of the car prior to beginning the dump, so that as it tipped, the weight of the load shifting to the down side pushed the car side outward on that side and allowed the load to slide out. |

The original car(s) of this series were 28 feet long and carried a load of 18 to 20 tons. This in a day when dump cars had only four wheels and carried five to six tons. No wonder Van Wormer’s cars were popular! But at the same time, this car had no brake gear rigging, and had no place to put it anyway. It is possible this doomed its use to nothing other than maintenance-of-way use. And it was followed very shortly by other tip-car inventions, including pneumatic-powered dump cars.