St. Louis Car Company - Page 2

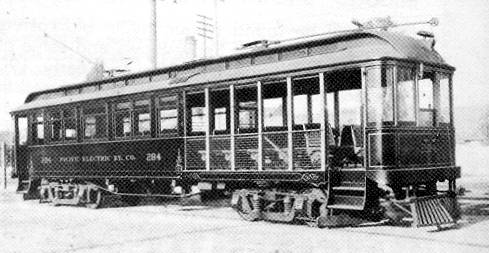

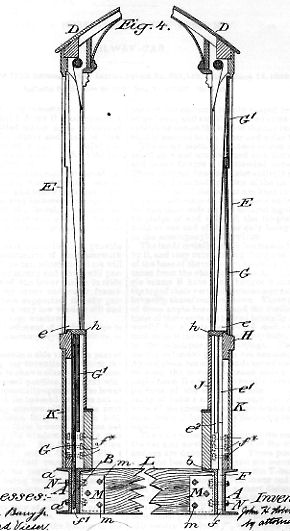

About this time, “convertible” cars were becoming popular. In those days before air-conditioning was even thought of, streetcar companies had to have two sets of cars: open cars for summer and closed cars for winter. For some time, cars were popular that combined open and closed areas, but this meant moving unneeded tare weight. It’s hard to say just when someone first had the idea of building a true “convertible” car as opposed to one that simply provided modest protection from inclement weather. But by the early 1900s there were quite a few different approaches. St. Louis’ approach was based on the ideas of John H. Robertson, Superintendent of the New York Third Avenue Railway Company. Robertson’s idea was to eliminate the usual heavy wooden side sills that supported the streetcar’s floor and substitute two channel iron beams in a back-to-back configuration like this ] [ with sufficient space between them that the oversize car windows could be lowered all the way down to the bottom of the frame (see below). Robertson received patent no. 621,142 (14 March 1899) on this idea, and subsequently sold the rights to St. Louis Car.

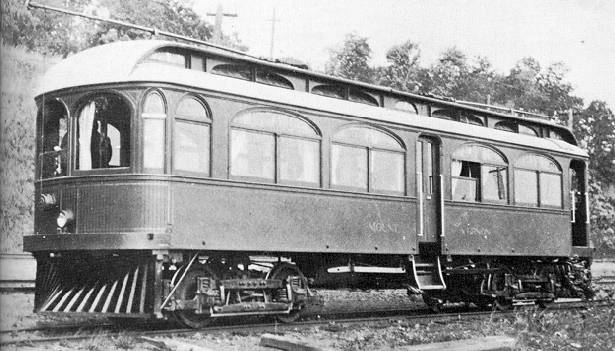

In 1903, Henry Vogel was promoted to a vice-presidency and given an assistant in the person of William Sutton, who had been President of the American Car Company until it was taken over by the J.G. Brill Company in 1902. Sutton was made General Superintendent of the company, specifically responsible for all the foremen in the plant. Much of 1903 was taken up with preparations for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair: the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The company’s exhibit contrasted the old and the new in transportation, with emphasis on the new, of course, which was none other than the streetcar! Included were cars built for New York’s IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit), Chicago’s North Western Elevated Railway Company, and several private cars: the Milwaukee and the Mabel. The Mabel was both exhibited and used to provide transportation to the elite visitors who were given private tours of the company’s facilities.

The car company’s main thrust during this time was to obtain foreign business, which it did quite successfully. But it also got into the automobile business, At the Exposition, a French auto company had been awarded a Grand Prize for its large, luxurious touring car, and the company began negotiations to build it in the United States. These negotiations and the accompanying preparations took several years to complete. But they matured at just the right time, as the stock market slumped badly in the first part of 1907, and orders for streetcars diminished. This made available the “overflow” plant: the former Laclede Car Company plant in downtown St. Louis. We’ll not chronicle the company’s struggles in the automobile business, nor the financial problems that beset George Kobusch during these times. If you are interested in these subjects, we recommend Young and Provenzo’s excellent History of the St. Louis Car Company. Actually, if you wish to know more about the St. Louis Car Company at all, you will have to go to one or another of the excellent resources listed on the next page, as circumstances have forced us to cut short our efforts at this time. But this company had a long and distinguished history which is documented much better than most. Someday we hope to continue the story, at least through the end of the wood car era, which was not too far into the future for the St. Louis Car Company. |

||||||||