Springfield's FourDean, Packard & Mills

|

|

DEAN, PACKARD & MILLS,

|

| Facsimile of an advertisement from the 19 May 1849 issue of American Railroad Journal. |

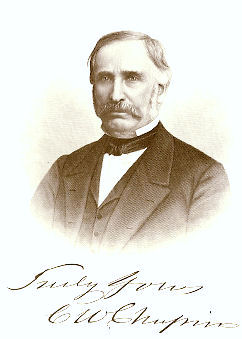

In 1848, “cousin Chester” (W. Chapin) and two other Springfield men, J.M. Blanchard and W.C. Averill established a corporation they called the Springfield Car & Engine Company, capitalized at $100,000: a whale of a lot of money for those days, equivalent to roughly $2 million today, but most likely nowhere near entirely paid-in. They began by building 4-wheeled work cars for the Western Railroad, one of many in which “cousin Chester” had an interest. And that first year they also built a locomotive for the Old Colony Railroad.

About that time, another company was started, or simply began building railway cars: Nettleton & Bartlett. We have found nothing about this firm other than what is disclosed in the advertisement it ran from late fall of 1849 to about August of 1850. But these ads contain a testimonial letter from the Western Railroad dated 1849, and mention cars being “in use for the last 12 months,” suggesting they were in business (or simply building cars) from sometime in 1848.

Nettleton & Bartlett’s advertisements said they manufacture railroad cars “in all their various branches” and especially “passenger, post office, baggage, freight, and hand cars,” including “an entirely new description of dumping cars for grading roads, transporting coal, brick, stone, and other kinds of freight.” These dumping cars are the ones “in use for the past 12 months.”

We can’t help but wonder if these were the same general type of 4-wheeled work cars built by Springfield Car & Engine, since they were built for the same railroad. Did Nettleton & Bartlett simply see an opportunity to “expand” into more lucrative prospects? If you have information about this company, won’t you share it with us?)

The End of the Beginning / The Beginning of the End -1848

But as Dean, Packard & Mills were “expanding,” Springfield Car & Engine was either shutting down its entire works, or at least the car-building part of it, as the Wason brothers, who were looking to expand their own business, bought the machinery of the Springfield Car & Engine Company’s car department, leased the shop for five years, and immediately began to build all kinds of cars, giving special attention to passenger cars. With more appropriate facilities, the Wasons’ business increased rapidly and they began to make a name for themselves.

But one or more of the following began to have its effect —

| o | lack of capital |

| o | overblown enthusiasm for a too-small market |

| o | effective competition from the Wasons |

By 1849, the Dean, Packard & Mills partnership was apparently breaking up. We can’t know that for sure, but the evidence certainly points that way. Elijah Packard had become involved with Eliam Barney and Ebenezer Thresher in setting up the Dayton Car Works at Dayton, Ohio. Begun as Thresher, Packard & Company, it would eventually become Barney & Smith. Though Packard appears to have stayed less than a year, when he “returned,” it was not to Springfield.

In mid-1850, Dean, Packard & Mills failed. Assets were supposedly in excess of liabilities—on paper—but not in reality.

By August of 1850, Nettleton & Bartlett’s advertisements had disappeared from the American Railway Times. We don't know what became of that firm. Perhaps they went back to building carriages and wagons or whatever it was they did before their brief foray into railway car building.

Sometime around 1850/51, Thomas Wason’s brother Charles left to set up his own car-manufactory in Cleveland. (Looking for greener pastures?) Thomas Wason took in several new partners, and the business was reorganized as the T.W. Wason Company. It is very likely this infusion of new capital, coupled with an established reputation, that kept this business alive while all the rest were in decline.

In 1851, an advertisement in the American Railway Times for 20 March 1851 offered, “For sale: six eight wheel house freight cars—Coupled and ready for use. Also, for sale or rent the Machine Shop and Car Factory recently occupied by Messrs. Dean Packard & Mills, with a Twenty-four Horse Power Engine in the same.”

In 1852, Averill and Blanchard, who seem to have been the “mechanical” end of the Springfield Car & Engine Company either hired or took as a partner C.W. Kimball, who took over the locomotive shop. That same year, they found a new financial backer, Eleazar Ripley (apparently in place of Chester Chapin. The firm was reorganized as the Springfield Locomotive Manufacturing Company. [No more cars!] Unfortunately, Ripley died a month later.

Under the category Railway Car Manufacturers in the business section of the Springfield city directory for 1851-1852 it says, “The only car manufacturing establishment in Springfield is now carried on at the old car and engine company’s building near the depot, by Mr. Thomas W. Wason.”

Epilogue

By 1853, Isaac Mills, formerly of Dean, Packard & Mills, is known to have entered his father-in-law’s coal business, of which he would eventually become owner.

In 1853, William C. Averill of the Springfield Locomotive Company was killed when he became entangled in a drive belt. (Remember, in those days machines were driven by long exposed leather belts connected to an overhead main-shaft that was, in turn, driven by a steam engine, or more likely in this case, by a water wheel.)

In 1854, Caleb Parker, who reportedly had worked for Dean, Packard & Mills, bought Ebenezer Thresher’s interest in E. Thresher & Company, the predecessor to Barney & Smith and the same company that Elijah Packard had helped start in 1849, and reportedly moved the machinery once owned by Dean, Packard & Mills to Dayton, Ohio, where that firm became Barney, Parker & Company.

By the fall of 1855, Blanchard and Kimball of the Springfield Locomotive Company had produced a total of 19 locomotives. In March of the following year, they declared bankruptcy and Blanchard left. The Receivers were unable to put the business back together, and the company’s assets were sold at auction to Stephen C. Bemis (Bemis & Company) who shortly thereafter sold out to the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad.

And the T.W. Wason Company went marching on . . .

For More Information —

Bliss, George. Historical Memoir of the Western Railroad. Springfield, MA: Samuel Bowles & Company, 1863.

Historical data concerning the chartering and construction of the Western Railroad and its extension into New York state. Also includes the economics of the railroad up to 1862.

In 1830,

In 1830,