MLS&W #63 and Art Nouveau

by Glenn Guerra, ©2001 MCRHS

In previous articles about the Milwaukee Lake Shore & Western #63 we have discussed the influence of Edward Colonna and the Art Nouveau style on the car’s interior. At the time #63 was built, Colonna was a young man and the Art Nouveau movement not much older. By 1888 the Art Nouveau movement was not well defined, despite its 30-year existence. The style had not been developed into the form we most think of it today, but it was here and the ideas were forming.

Since the 17th century, architecture was heavily influenced by the classic architecture of Rome and Greece. In these early forms of revival styles, it was considered very important to adhere to the proportions and shape of the buildings of ancient Rome and Greece. These influences in America were evident in the popular Federal Style of architecture during the colonial period, and the Greek Revival that followed. After the Civil War there was a great explosion of design influences. These included Italianate, Queen Anne, French Château, Eastlake, Art Nouveau, and even the Craftsman Style. All saw some use in railroad cars of the period following the Civil War and WWI.

MLS&W #63 is interesting in that it is an early example of the Art Nouveau influence. It is also interesting from the standpoint of the people involved with the design of the car. When #63 was built, young designer Edward Colonna worked for the Barney and Smith Car Company. He left Barney and Smith very soon after. After a short time in Canada he went on to Paris and became one of the central figures of the Art Nouveau movement of the 1890’s. Despite his departure from the Barney and Smith Car Company, they did not abandon their use of the Art Nouveau style. The influence continued until the end of wood interiors in their cars. At Mid-Continent Museum, later examples of Art Nouveau influence upon car interiors can be seen in the Soo Line coach #957 built in 1907, and the Great Northern #3261, built one year prior in 1906.

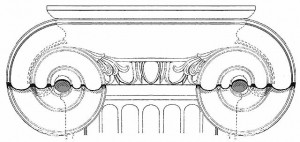

The Ionic-inspired capital and pilaster between the windows of Milwaukee Lake Shore & Western #63 at Mid-Continent. Compare with the classical Ionic capital and fluted column.

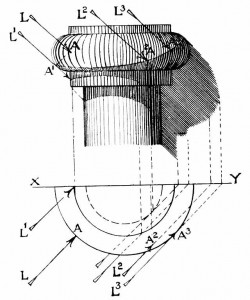

Some of the specific elements of #63’s interior design are interesting when viewed in relation to the movement of the times. The capitals between the windows are a stylized version of the classical Ionic Capital. The proportions and shape of the Ionic Capital are very specific. The designer of MLS&W #63 softened the edges and added a small shape in the center that resembles a sprouting seed.

One of the central themes of the Art Nouveau movement was the influence of nature and natural forms. While still not ready to abandon classical teachings, the designer was nevertheless exploring new ideas. Another natural form is the molding just above the capital. This molding at the top of the wall is a very gentle ogee type of curve. In classical architecture this frieze would have been flat or decorated with carving. The shape used in car #63 softens the hard line of the classical frieze. The shape is almost undetectable until it meets the corner of the washroom. At this point the molding is returned to the wall and we can see its profile.

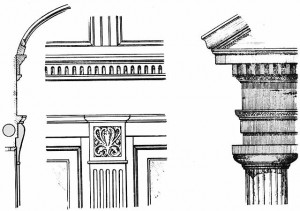

This illustration from Railroad Car Journal, March 1893, shows the relationship of the interior of a railroad car, pictured on the left and center, to the classical architecture pictured on the right. It appeared with an article by Archer Richards on railroad car design.

The capital at the corner of the washroom (see below) is a stylized Corinthian capital. Again the designer has taken liberty with classical designs. The location has been modified. Classical conventions would position the capital below the frieze. Here the designer has moved the capital up and used the profile of the frieze molding to frame it. The classical Corinthian capital uses acanthus leaves for decoration and has a flat top. MLS&W #63’s designer used the acanthus leaves but softened the rigidity of the flat top. All of these designs are a departure from the pure classicism but the designer was still essentially modifying existing designs.

The corner of the washroom of MLS&W #63 at Mid-Continent. Note the stylized Corinthian capital and its location. Also note the shape of the Frieze at right and how it is returned to the wall.

This is a classical Corinthian Capital. Note the acanthus leaves and the abrupt top of the capital.

The carving above the end doors is the sign of things to come. It bears no lineage to classical architecture and is more representative of Art Nouveau’s direction. It is an organic form with no lineage to classical architecture.

The design of railroad cars in this era was not just confined to Edward Colonna and Barney and Smith Car Company. The railroad publications of the day were full of articles on car design. The trade organization Master Car and Locomotive Painters Association was formed in 1870 and was very interested in decorative design. One of the founders of that group was Warner Bailey of the Boston & Maine Railroad. By 1888 when Colonna was beginning his career, Warner Bailey was the elder statesman of the painters association. During the 1890’s, nearly every issue of Railroad Car Journal included some design work of Warner Bailey. He would submit stylized alphabets and ceiling decorations. The style of his work was easily recognizable; some might have called it Victorian. It was indeed, but this was America’s version of Art Nouveau.

The carving above the entry doors of MLS&W #63 at Mid-Continent is seen here. This sample is the car’s most indicative of the direction Art Nouveau style was heading.

From Railroad Car Journal, Volume VII, number 2, April 1897, these designs were submitted for publication by Warner Bailey. He was the elder statesman of the Master Car and Locomotive Painters Association. His designs demonstrate some of the American interpretation of Art Nouveau.

These designs were submitted to Railroad Car Journal by G.O. Nelson. Note the flower growing directly out of the stripe. These designs show the American interpretation of Art Nouveau. They appeared in the September 1897 issue.

These designs were submitted to Railroad Car Journal by G.O. Nelson. Note the flower growing directly out of the stripe. These designs show the American interpretation of Art Nouveau. They appeared in the September 1897 issue.

Another designer by the name of Archer Richards wrote a three-part article in Railroad Car Journal during the spring of 1893 about car design. It read like a beginning art course with discussions on shadow, shading, and color. In Richards’ article, one could see the influence of classical architecture and how he adapted it to railroad car interiors. Another design sent into Railroad Car Journal for September 1897 was from G.O. Nelson. His designs show plants growing out of the outline for a car’s ceiling panels. Art and design were very much on people’s minds during the last half of the 19th century and the links to nature were very much a part of it. All of this played into the Art Nouveau movement but it never really had a defining character. The interpretation of Art Nouveau varied from country to country. This variance though has some interest to us here at Mid-Continent.

The lettering on the washroom from the Great Northern coach #3261 at Mid-Continent. Note the serifs on the letters and the general oriental influence.

After Colonna left Barney and Smith Car Company, he went to Canada and finally to Paris. In Paris he went to work for Samuel Bing at the La’Art Nouveau. Bing was one of the people who truly defined the Art Nouveau style in Europe. He was an art dealer and orientalist. This connection is of the greatest interest to Mid-Continent. Bing’s designers–Colonna was one of them–were influenced by the oriental art objects that Bing sold and collected. The work that came out of Bing’s studios was distinct from that produced by the studios in Nancy, France.

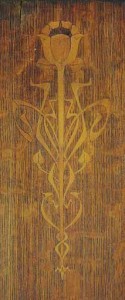

Inlaid woodwork design used between window openings in Soo Line coach #957 at Mid-Continent. This is the Tulip motif used extensively in European Art Nouveau. Note the shape of the leaves under the bud. There is a strong oriental influence in Art Nouveau.

The inlaid woodwork design used in GN #3261 at Mid-Continent. Similar to #957?s, it is a highly stylized tulip motif common to Art Nouveau design.

With this in mind, let us compare the decoration in Soo Line coach #957 with that of the Great Northern #3261, both at Mid-Continent. Ornamentation inside the #957 resembles the tulip, a common theme. The leaves under the flower reveal an oriental influence. The shape is very similar to what would be produced with a Chinese brush. The abrupt point and flowing shape also has the influence of Chinese writing.

The design on the wall of GN #3261 also reveals more of the European influence than American. The design is again a highly stylized tulip with shapes reminiscent of Chinese brush work.

The examples of European Art Nouveau styling found at Mid-Continent were more prominently embraced by the Barney and Smith Car Company and for a longer time than the other builders. The real questions here are did someone at Barney and Smith influence Colonna or did his influence at Barney and Smith continue long after he left? There is reason to believe that his influence continued long after he left. The designs of the 1906-1907 cars were designs of the maturing of Art Nouveau and are very much of the oriental influence of the Bing studio. It is conceivable that the interior designs found in Soo #957 and Great Northern #3261 are Edward Colonna’s from his days at the Bing studios. The Barney and Smith Car Company may have been hiring or buying Edward Colonna’s designs for many years.