By Glenn Guerra, ©2001 MCRHS

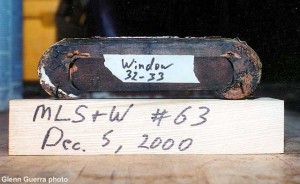

One of the questions visitors ask us when they come to an open house at the Car Shop is how were these cars built. Unfortunately there are no existing Barney and Smith Car Company records from the time when the Milwaukee Lake Shore & Western #63 was built. There is very little documentation from any of the car builders of this period. So to answer the question, we must piece together information from railroad trade journals, some company records, and information obtained from the car itself.

The Trade Journals

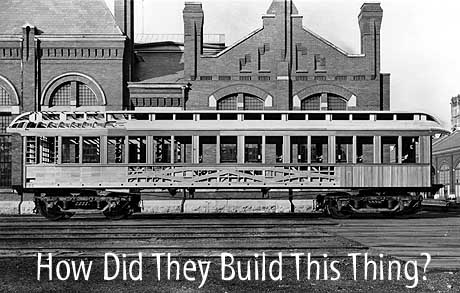

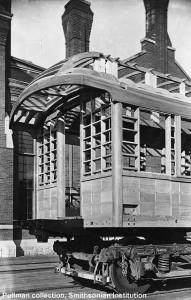

The Pullman photos on this page were taken of a car built by Pullman in 1889. This car was a standard 17-window coach identical to MLS&W #63. Pullman built the car for display to show its design and construction. Note the use of solid blocking which was not used in the MLS&W #63. Pullman Collection, Smithsonian Institution.

For this era, our best trade journal sources are magazines called the National Car and Locomotive Builder and Railway Car Journal and a book entitled Railway Car Construction. Both magazines covered the design and construction of railroad cars. During the late 1880’s, William Voss, who at the time was a master car builder with the Burlington Cedar Rapids & Northern, wrote a number of articles for the National Car and Locomotive Builder.1 In 1892 he was enticed to write a book on railway car construction. This book, Railway Car Construction, is the only such publication written on the topic for this era. What interests us most at Mid-Continent is that at the time Voss wrote his book in 1892, he was then employed as the Assistant Superintendent of the Barney and Smith Car Company.2 Therefore some of his writings in 1892 could help us understand our car built just four years earlier in 1888.

What is most lacking in these articles and books, however, is the details and progression of construction. We know the woods most commonly used and where the parts are located but not the order they were installed, fasteners used, joints used, and the method of forming the parts.

Company Records

Some company records would be of help but they do not exist and may never have existed. The few company records that do exist are not specifically related to construction but are contracts for the purchase of cars.

Some company records would be of help but they do not exist and may never have existed. The few company records that do exist are not specifically related to construction but are contracts for the purchase of cars.

One such record is the handwritten order for the Duluth South Shore & Atlantic Railroad #213, which was built by the Jackson and Sharp Car Company in 1887.3 This car is also located at Mid-Continent. The order indicates the five cars were produced and shipped in 2½ months. This would seem to indicate that there was some standard design and tooling utilized to speed up production. We see other evidence of this in the quantity of cars that were assembled by all the builders in a year. For example, in 1888 when the Milwaukee Lake Shore & Western #63 was built, 2,471 cars were constructed that year in the entire United States.

Car Information

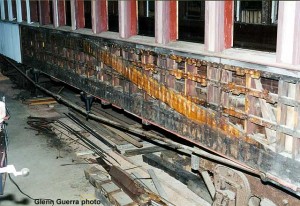

The side framing of the Milwaukee Lake Shore and Western #63 as we found it. Note the lack of blocking and other details found in the Pullman car.

One of the triangular “glue blocks” used to support the siding on the car in lieu of solid blocking. The Pullman display car also used similar blocks (as seen in the photo on the opposite page). Photo by Paul Swanson.

Our last clues about the construction come from the car itself as we rebuild it. Our pictures and notes are recording the construction sequence, materials used, machines utilized, and workmanship. Following are some examples of our findings.

Let us begin with the basic structure. The car is built primarily of wood. Yellow Pine is used for the wall posts. This is a departure from the more common practice of using Ash for these parts. The woods used are mentioned in the trade journals and William Voss’s book. However, what we see on the cars does not always agree with the written material. We must therefore record our findings for historical purposes.

Why did Barney and Smith use Yellow Pine for these parts? Studying the trade journals from this era, we see a desire for industry to be self-sufficient. We also see that the Barney and Smith Car Company had relations with an Atlanta, Georgia lumber baron named George Gress.5 This relationship culminated in Barney and Smith Car Company acquiring the mill, forest lands, and lumber railroad in 1905. These forest lands were in Georgia where large stands of Yellow Pine were located.

We now have a little more insight into the working of the car company. If they were dealing direct with a mill in 1888 that was cutting the Yellow Pine for the car sills, it may have been prudent to buy the rest of the production and use it for other framing on the cars they built. The Yellow Pine forests were also very close to Dayton, Ohio, which would keep transportation costs lower. This lumber may have been cheaper than buying Ash on the open market. The use of the Yellow Pine in the car’s wall posts was most likely an economic decision rather than a design decision.

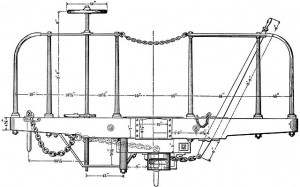

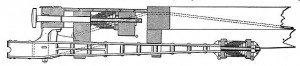

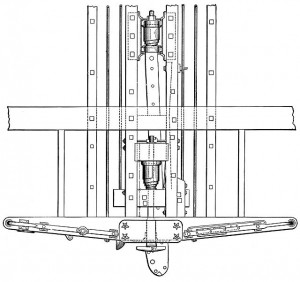

Also regarding the structure was the construction of the end platform and Miller Hook coupler. We went to the Nevada State Railroad Museum to measure the Virginia & Truckee #18. This car was built by Barney and Smith in 1890 and is similar in many dimensions to our MLS&W #63. The V&T #18 still retains its original platform on one end and some of the parts from the Miller Hook coupler. We compared the dimensions of the V&T #18 to the remains of the MLS&W #63 and found that the platforms were most likely the same dimensions. We also found that the dimensions match the drawings in William Voss’s book (see below). This may be more than a coincidence since at the time of writing his book, Voss was working for Barney and Smith Car Company.

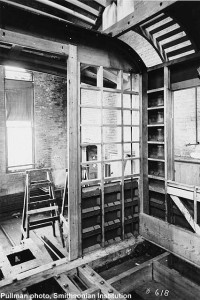

The grooves (indicated by arrows) in the clerestory sill at this location at the end of the car were cut using a handsaw and chisel.

This part was cut and fit at the site as opposed to being pre-manufactured at some other location of the plant. The grooves held the deck roof ribs in position.

On #63’s framing parts removed for repair, we noticed the tool marks. For example the window sub sill on the left front corner of the car had to be replaced. The notches in the sill to fit around the body posts were cut by machine. We know this from the small pointed groove at the cheek and land of the notch. This mark is from a machine cutter head used at this time and only replaced recently in woodworking. These marks contrast with the marks on the grooves that were cut in the blocking on the clerestory to locate the deck roof ribs. Here we see the use of a hand saw to cut the cheeks of the groove and a chisel to clean out the land (see below photos).

We now begin to see the different workers involved in building the car. Some of the components, such as the window sub sill, arrive in the erecting room as pre-finished components from the mill shop. Other components such as the blocking, were cut at the site by the carpenters who assembled the car.

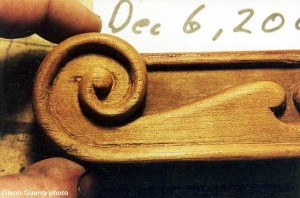

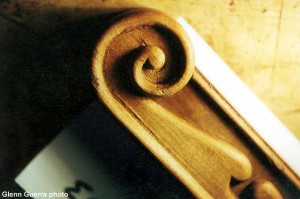

On the interior of the car, the capitals on the pilasters between the windows appear to be intricate carvings. They are not. Remember this car and the two others in this order were most likely finished in a few months. There are fourteen of these capitals per car, multiplied by three cars, resulting in forty-two capitals to fill this order. On closer examination we see that the capitals are made from two pieces. The lower piece is a straight molding. In one hour, one man could have fabricated a sufficient amount of this molding to supply all the cars. The upper piece with the rams’ horn was most likely done on a carving machine. We suspect this because of the small mark on the inside of the rams’ horn. This mark was the result of cutting out the small fillet that was there when the part came out of the carving machine. Again, one man could produce all forty-two pieces in less than four hours. The next cutting operation on these parts was to relieve6 the back of the upper piece so the lower piece could be installed. This is a fairly simple operation on a wood shaper.

The back side of the capital. The capital was actually made of two pieces of wood, the larger curved main carving, and the flat insert that formed the base of the capital. This construction made the capital very easy to mass-produce.

The mark on the inside of the volute is from the hand chisel used to clean out the fillet left after this piece was cut on a carving machine.

From knowing what machines were available and looking at the construction and tool marks, we can learn much about the manufacturing of this car that is not recorded or may have never been recorded.

Workmanship is another aspect of the car’s construction we can study. Discrepancies noted in the construction of the car tell us there a fair amount of the decision-making regarding the construction was most likely left to the worker doing the work. For example, between the body posts and the sidewall truss, it was not uncommon to block the area in with solid blocks of wood.

We see this on other cars at Mid-Continent and in photographs of a Pullman-built car from 1889. Pullman made this car for a display but it is not known where. These photographs are of interest as the display car was built in the same era as MLS&W #63, and is the same class of car–17-window coach. In this car, the body posts were blocked in solid before the siding was installed. On our car, the blocking is very random and not complete at all. Where there was no blocking, small triangular blocks were glued to the body post and siding from the inside. It appears there may have been no official policy or design for installing these blocks at Barney and Smith Car Company when our car was built. On the hand-cut grooves mentioned earlier, we see some variation in spacing and depth. Also the removal of material with a chisel was not done very carefully. The location of the grooves may have been left up to the carpenter and the finish of the groove may be an indication of limited quality control.

By observing these types of things on MLS&W #63, and comparing what we see to what we read, we may gain a better understanding of how this car was built 113 years ago. The findings are also the justification for all the study, documentation, and sample collecting we perform on this car. This project is only the beginning of the work to be done at Mid-Continent. There are seven different railroad passenger car builders represented in the collection at Mid-Continent spanning from 1864 to the end of the wood car era. This collection and the material gleaned from it is one of the finest single source examples of the wood passenger car and its construction in the country. The methods used in the MLS&W project are the results of lessons learned from other projects and will be applied to the next.