Local History

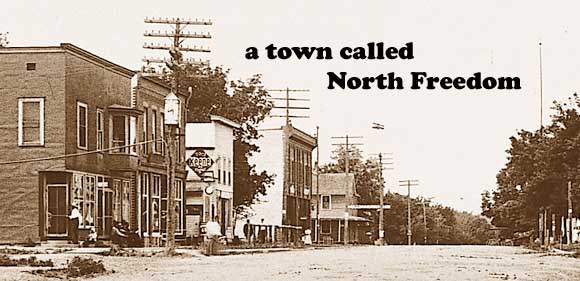

A Town Called North Freedom

(text and photos from “Whistle on the Wind” ©1997 MCRHS, updated 2020)

It all began back in 1848 when Samuel Hackett acquired some land. By 1856 his son John built the first house at the crossroads, and as others followed, this little community became known as “Hackett’s Corners.”

In 1871, a Mr. G.W. Bloom purchased 27 acres of land along the North Western Railway’s survey, and in 1872 he persuaded the C&NW to build their depot on his land. The tiny village became known as “Bloom” or to some as “Bloom’s Station.” This new name met with much dissatisfaction among the early settlers and a compromise was finally reached.

Since the village was located in the northern section of the Freedom Township, it became “NORTH FREEDOM.” Then during the first iron mining boom in 1887, the name changed again. The new moniker of “Bessemer” met with much confusion. The village’s mail and freight were often mistakenly routed to Bessemer, Michigan, another station on the C&NW’s vast system.

By 1890 the village name returned to North Freedom, and within three years it was incorporated.

As the second iron mining boom took hold in 1900, and for the next fourteen years, North Freedom became the center of activity. New stores and homes were built to serve the area. North Freedom was soon graced with a fine new water system, a volunteer fire department, and in September of 1903, the village’s first edition of their weekly newspaper boasted electricity coming to town!

North Freedom is alive and well today. But with bigger businesses and industries, residents have shifted their working environment to cities like Baraboo, Reedsburg, and even Madison, while still living in North Freedom, in many of the houses built by the early settlers.

The Coming of the Railroad

The Chicago & North Western Railway (C&NW) was the city of Chicago’s first railroad when its predecessor Galena & Chicago Union built a few miles of track west from the Chicago River in the summer of 1848. The line was a success and quickly grew into a vast network of rail lines in Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

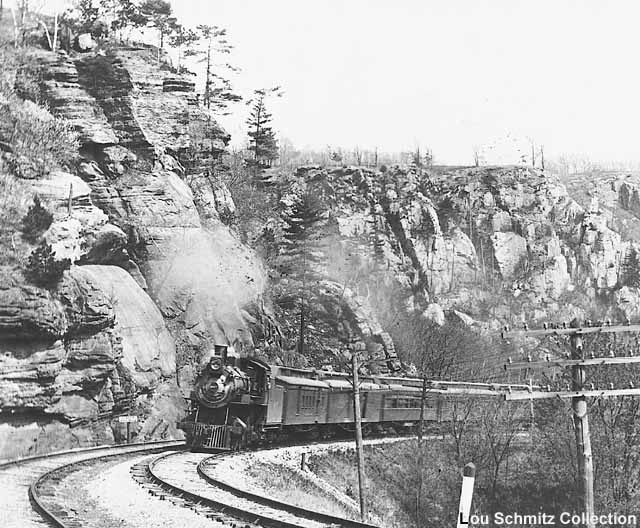

Seeking a transportation link to the outside world, Baraboo area settlers obtained a charter from the Wisconsin state legislature for the Baraboo Air Line on March 8, 1870. The name referred to the straightness of the route, not the mode of transportation. The new line would build from Columbus, Watertown, or Madison, through Lodi, Baraboo, and Reedsburg, to Tomah or LaCrosse. Less than a year later, this fledgling railroad was purchased by the C&NW. With the financial backing of the big road, the route was completed from Madison through the scenic Devil’s Lake and Wisconsin River Valley, Baraboo, North Freedom, and Reedsburg to Elroy by August of 1872. Less than a year later, the line was completed west and became the C&NW’s first route connecting Chicago with the Twin Cities.

The line boomed and Baraboo prospered as a new division headquarters. By 1892, almost 500 railroad employees lived at Baraboo. Dozens of freight and passenger trains passed through daily. To boost capacity, the railroad added a second mainline track (called double-track), built new stations (Baraboo received its new brick station in 1902, Reedsburg in 1906), and buying new locomotives and cars.

But the heyday would not last. In 1911, a new more direct mainline north of the Wisconsin River valley was completed from Milwaukee to the Twin Cities by the C&NW. From then on, the Baraboo line declined. The railroad’s shops at Baraboo closed in 1924 as work was moved to Madison. And by 1933, the Madison Division headquarters were moved out of town. In 1954, the mainline was reduced to a single track again. Passenger train service–down to a single train a day–ended unceremoniously in 1963. In the mid-1980s, track was abandoned west of Reedsburg, making the Baraboo line a dead-end railroad with only local service. No longer could trains run through to the Twin Cities and west. Today, even the railroad companies have changed. C&NW was absorbed into the vast Union Pacific system in 1995. Beginning in October of 1996, Wisconsin & Southern Railroad leased the track, operating only a few freights a week from Madison, and hauling rock ballast from a quarry at Rock Springs for use on the C&NW/UP system during the summer. The Baraboo line’s rise and fall echoed that of rail transportation in general throughout the Midwest–its vital importance as a source of transportation and a way of life diminished with the advent of modern highways and airplanes.

North Freedom is alive and well today. But with bigger businesses and industries, residents have shifted their working environment to cities like Baraboo, Reedsburg, and even Madison, while still living in North Freedom, in many of the houses built by the early settlers.

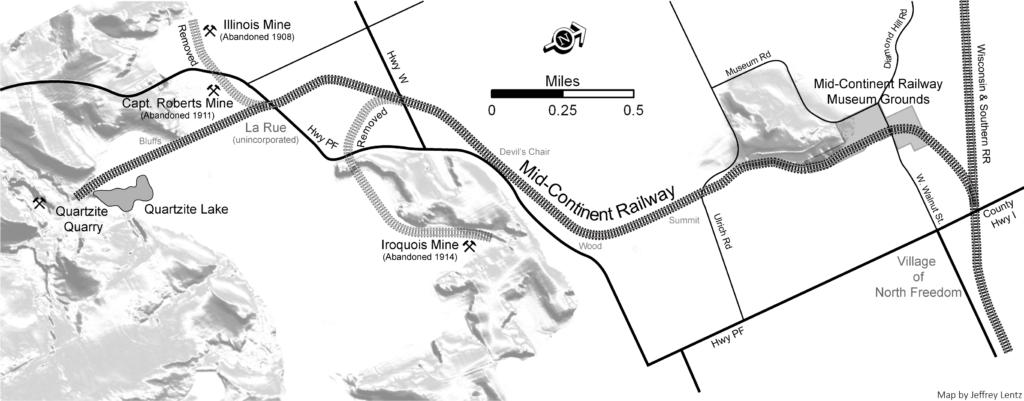

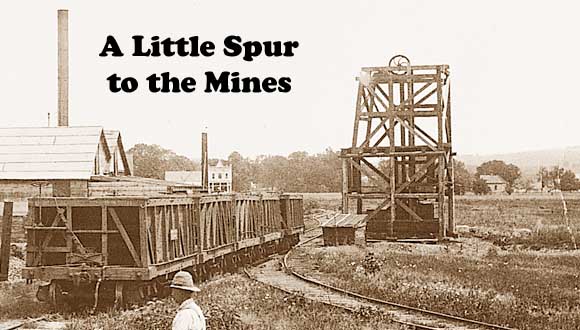

A Little Spur to the Mines

The tale of the Quartzite spur began over one hundred years ago, in the mid-1880s. For some years, a deposit of low-grade iron ore near the present LaRue village site was mined for use as paint pigment. By 1887, the Douglas Iron Mining Co., under the direction of Mr. F.T. Brewster, was probing for higher grade ores nearby, all with little success. The remaining years late in the 19th Century were completed with mining limited to the low-grade paint pigment ore.

By 1900, a man and a better machine came to the area which would eventually bear his name. W.G. La Rue, with experience on the Minnesota iron ranges, brought the diamond drills. La Rue and his partners incorporated the Sauk County Land & Mining Co. in 1902 and soon drills located samples of 53 percent iron several hundred feet below the surface. By 1903 the mining boom was on with land leased to the Deering-Harvester Co.

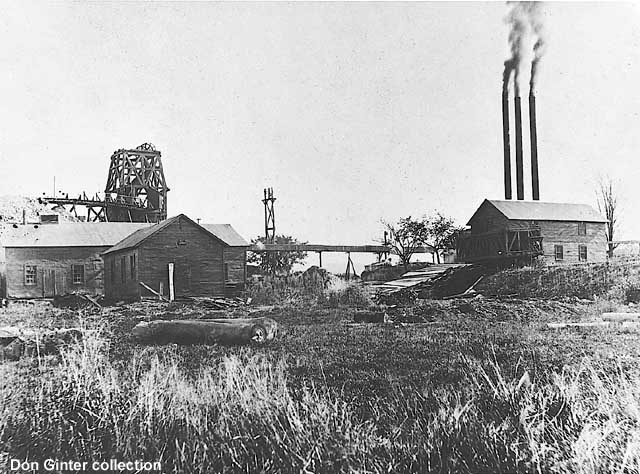

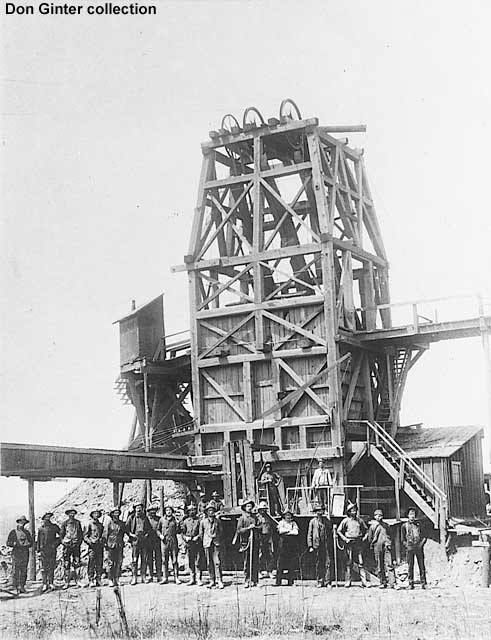

It looked like a sure thing. Three mining interests were active in the area, with one already producing, prompting the Chicago & North Western Railway to act. By December 1903, three and one-half miles of track extended from North Freedom to the Illinois Mine just west of the present La Rue townsite. The red rock came up and cascaded into the short wooden ore cars. Over the rails, it was carried away to Harvester’s great furnaces in Chicago.

Wishing to further capitalize on the area mining fever, W.G. La Rue and his partners incorporated the La Rue Townsite Co. at the end of 1903. Sweatstained, ore-caked miners were soon able to swap their hard earnings for a stein of beer in one of two saloons. A hotel and a row of wooden company-built cottages soon housed Norwegian, Swedish, and Finnish miners. A church to reclaim the rowdy miners’ souls on Sunday and a store were established–La Rue was on the map. Up and down Illinois and Wisconsin Streets, and over on Deering Avenue, miners set their life to the sound of the hoist whistle.

But there was water down in the mines, lots of it; the red earth sweated and oozed. The ore was rich but the mines could not compete with the Upper Michigan and Minnesota iron ranges. Water filled the mine shafts despite constant pumping; the cost was too high and the last mine closed in 1914. La Rue quickly became a ghost town. The miners left, buildings fell into ruin, and the rails rusted.

With the onset of the first World War, need arose for an extremely hard quartzite rock. At a place called Rattlesnake Den, a mile south of the remains of La Rue, laid a large deposit of quartzite. In the fall of 1917, rusty rails creaked under work trains bringing in new rail and ties. Soon new traffic rolled north from the Baraboo Range to the North Western main line.

For 44 years quartzite rolled from the crushers into railroad cars. The Harbison-Walker Co., owners of the operation, shipped the material to plants in Ohio for blast furnace lining and firebrick making. But changes in steel making reduced the demand for quartzite and by 1962 this, too, was over. The quarry reopened in the 1990s to serve local construction projects and sees occasional use – however, all rock is delivered by trucks.

Rediscovering the Past

At the iron mine sites, the only remnants today are a few building foundations, tailings piles, and the mine shafts. Some shafts were capped for safety reasons, but others simply filled with water, eventually taking on the appearance of small ponds. The tunnels hundreds of feet below went unseen by human eyes for more than a century until a team of maritime archeology scuba divers from the Wisconsin Historical Society explored the depths.

What the divers discovered was a moment frozen in time… the fateful day over a century ago when the mine’s water pump failed. A toolbox could be seen next to the water pump where workers had been attempting to make the pump operational. Pickaxes, a mine cart, drills, tallow candles, and other items were left where they lay as the workers evacuated to the surface. The rushed evacuation of the mines left behind an unadulterated example of how an underground iron mine of the early 1900s appeared and operated.

The Freedom Mine is the only known archaeological investigation of a submerged mining site, and its remarkable preservation made possible by its inaccessibility helped the Freedom Mine earn the mine a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in June 2020, joining Mid-Continent’s Chicago & North Western #1385 steam locomotive.

Videos of the Dives

University Place: Diving the Flood Mines of Baraboo’s Iron Range

For a first-hand account of the dive into the abandoned mines, watch Maritime Archaeologist Tamara Thomsen’s presentation at the University of Wisconsin titled Diving the Flooded Mines of Baraboo’s Iron Range.

Video by PBS Wisconsin’s University Place

Dive Into the Captain Roberts Mine

Video by John Scoles

Dive Into the Illinois Mine

Video by John Janzen