‘Steam & Steel’ Album Benefits Steam Restorations

Fundraising at Mid-Continent Railway Museum has taken on a more harmonious tone with the release of an original music CD entitled Steam & Steel: Songs of Railroad’s Golden Age. A collection of ten railroad themed songs, including nine original compositions by Mid-Continent member Ken Hojnacki, performed by Grammy Award-winning bluegrass artist Laurie Lewis and her band, they range in style from bluegrass to country to folk.

Order yours now from our Online Gift Shop or pick up a copy at the depot ticket window.

Steam & Steel Album (CD)

Buy nowAll proceeds directly help Mid-Continent’s steam program.

The Stories Behind the Songs of Railroading’s Golden Age

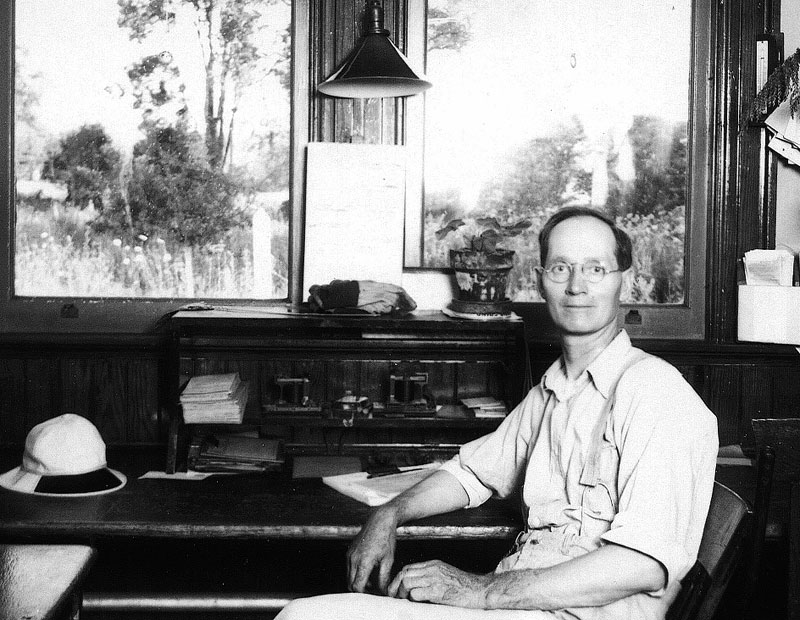

My love of trains began at an early age, growing up in my hometown of Auburn, NY. My sister had an American Flyer train set which was only brought out at Christmas. And I marveled at the stories told by an uncle, who worked as a conductor on the New York Central. I indulged my interests in trains by collecting models until I was old enough to become involved with full-sized trains at the Rail City Museum in Sandy Pond, NY. Cinders and coal smoke have been in my veins ever since.

All the sights and sounds of train operations have fired my imagination to the point that as the years went by, I merged my love of music with my love of trains and wrote the songs you hear on the Steam and Steel CD. While many popular songs use trains as part of their theme, my goal was to write about the people and their lives working the rails, while also celebrating the memory of some of the great railroads that are now gone from the scene. When inspiration hit, my wife Shirley would get a pad of paper and feverishly write down the words as they came.

Shirley’s comment, after hearing the unmastered version of the CD, was that “You can see the whole story unfolding in your mind.” And even though she has heard me sing these songs for years, she noted that Laurie’s arrangements and the heart put into them by each performer brought them to life at a higher level.

When I moved to Madison, Wis. in the late 1980s, one of the first things I did was to visit the Mid-Continent Railway Museum in North Freedom. After hearing for years through the hobby press about the members’ commitment to preserving the elements of railroad’s Golden Age, I just had to see it in person. I became a member and a volunteer, working my way up through the ranks of the train crew until I qualified as an engineer on July 21, 1996 on board the fabled ten-wheeler, the Chicago & North Western No. 1385.

And now, to underscore my devotion to the museum and our shared passion for railroad history, I have donated these songs to Mid-Continent for the sole purpose of creating a CD whose sales proceeds will benefit the museum’s steam restoration efforts. One hundred percent of the price, when purchased through the museum, will go into its Steam Fund to assure everyone who revels in the glory that is steam power that the trains will run for generations to come at the Mid-Continent Railway Museum. And I trust you will enjoy reading on to learn more about the stories behind each of my songs that comprise what has truly been a labor of love.

—Ken Hojnacki

Album Tracks

Old Saginaw

(Scott Huffman: guitar, lead vocal; Tom Rozum: mandolin, harmony vocal; Chad Manning: fiddle; Patrick Sauber: banjo; Laurie Lewis: string bass, harmony vocal)

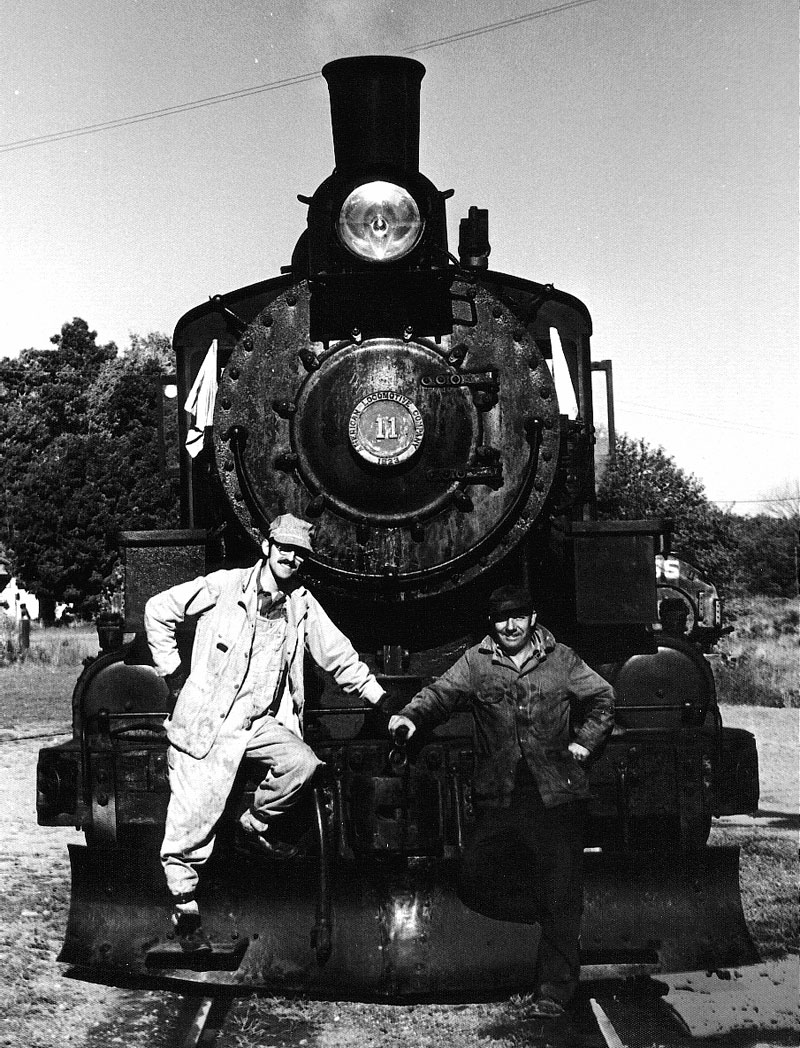

The Saginaw Timber Company No. 2 is a steam locomotive built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1912. She was used on logging railroads in the Pacific Northwest and later on tourist trains in Michigan before arriving at the Mid-Continent Railway Museum in 1982. An oil burner, she has been my favorite locomotive to operate at the museum. Her simplicity of Stephenson valve motion, sparse boiler backhead, Johnson bar and sleek boiler lines belie the power of those eight squat driving wheels. I like to tell visitors that after the Titanic sank in April 1912, they built the No. 2 in December of that same year as an equally impressive replacement. As the opening selection, the performance of this song sets the stage for the entire CD. This is exactly as I would have wanted this song to sound; lively, great accompaniment, and wonderful harmony. I couldn’t ask for a better rendition.

Have you heard about the Number Two, she’s called the Saginaw?

She worked out in the Northwoods and up in Mackinaw.

She hauled a lot of timber and man she done it good.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Old Saginaw, she’s rollin’ down the rail.

Old Saginaw, just keep out of her trail.

Can’t you hear her whistle blowin’? She’s soundin’ mighty good.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Mister Fireman watch your water and keep it nice and high.

Keep a close watch on your fire or she’ll spit that oil in your eye.

Hear the poundin’ of the drivers, she’s workin’ like she should.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Old Saginaw, she’s rollin’ down the rail.

Old Saginaw, just keep out of her trail.

Can’t you hear her whistle blowin’? She’s soundin’ mighty good.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

The lumber mills are quiet now, Mother Nature’s claimed her trail.

But the Saginaw’s still running on the old North Freedom rail.

She’s haulin’ folks, not logs today, but she still does it good.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Old Saginaw, she’s rollin’ down the rail.

Old Saginaw, just keep out of her trail.

For ninety years she’s done her job like Baldwin knew she could.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Old Saginaw, the workhorse of the woods.

Denver & Rio Grande

(Tom Rozum: mandolin, arch-top guitar, lead vocal; Laurie Lewis: guitar, vocal; Bobby Black: steel guitar; Andrew Conklin: string bass)

After a ride on the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, which is a remnant of the once vast Denver & Rio Grande narrow gauge network, thoughts of railroaders working in the rugged Colorado mountains to open up the West led to writing this song. It is meant to be an homage to late 19th Century railroading on this most celebrated narrow gauge line in the country. Steam trains still climb to Windy Point and Cumbres Pass on the Cumbres & Toltec line, while Durango & Silverton trains cling to narrow ledges above the Animas River on the way to Silverton so we can still experience the adventure depicted in this song. I like Laurie’s arrangement, even the change from my ending on a minor note on every verse except the last, which makes for a nicer sound.

High in the Rocky Mountains in the Uncompaghre Range

I was just a boy when I first recall those trains.

‘Twas then I knew what I had to do when I became a man,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

The work was hard, the winters cold, the summer harsh with heat.

Gold came down from Silverton, from Gunnison came sheep.

And down the way to Santa Fe through great, green timber stands,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

Looking down from Windy Point to the valley far below

I could see the little trains a battlin’ the snow.

Engines numbered 3 or more with smoke plumes tall and grand,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

Climbing over Monarch Pass on switchbacks, to and fro,

Oil trains to Farmington and Cumbres in the snow,

Silver, cattle, coal and more were carried from this land,

Carried on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

Over Cerro Summit and up through Marshall Pass,

Crested Butte, Monero, Chama, Wagon Wheel Gap,

Pagosa Springs and Ridgway in a circle cross this land,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

Here’s to the railroad men who toiled through rain and snow,

Mountain tops to valley floors, wherever rails did go,

The best of railroad men were found working hand in hand,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande,

Working on the narrow gauge, the Denver & Rio Grande.

Memories, Childhood Days

(Laurie Lewis: string bass, vocal; Scott Huffman: guitar; Tom Rozum: mandolin; Chad Manning: fiddle)

This song sprang from my Saturday mornings playing engineer in a certain living room chair that eventually evolved into actually running steam locomotives in both the US and China. The song includes all the things I think a youngster before my time might have experienced and that I longed to experience had I grown up in the steam era. Steam locomotives, crisp winter days with steam wafting from between the cars, the excitement of the local depot at train time – and all that has passed and gone. Driving past the New York Central’s Erie Boulevard station in Syracuse, NY and the Ontario & Western depot in Oriskany Falls, NY, both with highways running next to them, inspired the imagery of the “depot with its sad and lonely face” as the ultimate fate of so much of railroading’s past.

When I first heard Laurie’s rendition I almost didn’t recognize the song. My musical interest is more mainstream country than bluegrass, but listening to her version a couple of times made me appreciate the nostalgic tone set by her arrangement. It makes me think of a child’s fascination with the experience as it would have been in the here and now, then tempers the sadness of the last two verses with what my wife says is the violin crying in the background with the lyrics still evoking the child’s memory of a happier time. It presents this material in a whole new light and I’m loving it.

Through my frosty bedroom window I look out upon the world

And away off in the valley I can see the white smoke curl

And the yellow sun a-risin’ brings its warmth to greet the day.

Memories, childhood days.

As I rush to put my clothes on, hookin’ up my overalls

Still buttoning my jacket as I race out through the hall,

And I run down to the depot as I hear the whistle scream

Memories, childhood dreams.

As she pulls into the station hear the squealing of the brakes

And the panting of the engine, what a lovely sound it makes.

And the shining cars are gleaming in the early morning sun.

Memories, childhood fun.

The waiting folks all hurry from the warm potbellied stove

And they rush out to the platform in the freshly fallen snow.

And they board the cars with bustle and they’ll soon be on their way.

Memories, childhood days.

Then the big bell starts a-ringin’ and the whistle gives a shout

And the smoke and steam are spewing as the old train eases out.

And she slowly starts a-creakin’ down the tracks and far away.

Memories, childhood dreams.

Now I lie awake at night and hear the rumble of a train

And the glowing yellow headlight streaks across my windowpane.

And my mind goes on a journey to a place that’s far away.

Memories, childhood days.

So I go out to the depot with its sad and lonely face.

But a highway runs beside it, of the tracks there is no trace.

And I hang my head in silence as I slowly walk away.

Memories, childhood dreams, childhood days.

Wreck of No. 9

Written by Carson Robison

(Scott Huffman: guitar, vocal; Tom Rozum: mandolin, harmony vocal; Patrick Sauber: banjo; Chad Manning: fiddle; Laurie Lewis: string bass)

While not one of my songs, when I heard that Laurie suggested adding this classic ballad to the CD, I was surprised and somewhat taken aback. The first Hank Snow album I bought in the early 1960s was titled “Railroad Man” and contained this song. After learning to play guitar, it was one of the first railroad songs I learned and has always been a favorite. I am pleased to have my work in such good company.

On a cold winter’s night not a star was in sight

And the north wind came howling down the line.

With his sweetheart so dear stood a brave engineer

With his orders to pull old No 9.

She kissed him goodbye with a tear in her eye

But the joy in his heart he could not hide.

For the whole world seemed bright when she told him that night

That tomorrow she’d be his blushing bride.

Well the wheels hummed a song as the train rolled along

And the black smoke came rollin’ from the stack.

And his headlight agleam seemed to brighten his dream

Of tomorrow when he’d be goin’ back.

He sped around the hill and his brave heart stood still

A headlight was shining in his face.

So he whispered a prayer as he drew on the air

For he knew this would be his final race.

In a wreck he was found lying there on the ground

And he asked them to raise his weary head.

And this the message he sent as his breath slowly went

To a maiden who thought she would be wed.

”There’s a little white home that I bought for our own

Where I dreamed we’d be happy by and by

And I leave it to you for I know you’ll be true

’Til we meet at the golden gate, goodbye.”

Passenger Train

(Scott Huffman: guitars, vocal; Tom Rozum: arch-top guitar; Chad Manning: fiddle; Bobby Black: steel guitar; Laurie Lewis: string bass)

If you have ever ridden a passenger train, then you know how exciting it can be. Whether it is an old coach creaking along a branch line or a stainless steel streamliner gliding across the desert, the “glory and the grandeur of the passenger train” is a unique experience. Trips to New York City and Chicago on the New York Central and Erie Lackawanna railroads and to California on the Santa Fe and the Union Pacific lines introduced me to crisp linens and heavy silver in the diners (which led me to working first class service on trains at Mid-Continent), and the friendly and sometimes not so friendly, train crews and Pullman porters. This song recalls these experiences and highlights the anticipation of waiting for a train, the adventure of meeting new people and experiencing new things. Then it segues into a nostalgic recollection of famous passenger trains of years gone by. Scott has a great voice with a nice inflection for these lyrics. And a lyric change to reference “the Golden Age” in the first verse was Laurie’s suggestion to give it a nice tie-in with the CD’s title.

Listen folks and I’ll tell you my tale of the Golden Age of the big iron rail.

Life was different in days gone by. Didn’t have cars and no one could fly.

If you needed to travel from here to there free from worry and free from care

The way to travel and ease your brain was on a railroad passenger train.

The railroad depot was the center of town. That’s where all the young boys hung ‘round,

Waitin’ to wave to the engineer or watch the conductor with his stately air.

The big bell rang and the whistle screamed, to run an engine was every boy’s dream;

A promise of adventure that always came with the haunting sound of a railroad train.

You paid your fare and you boarded the car, your neighbor asked you are you traveling far.

Train started up with nary a jar, relaxed in your chair in the parlor car.

Dinner in the diner in high class style, rolling at 70 all the while.

The food was great and the service the same, on a railroad passenger train.

The conductor called “Tickets!” walkin’ down the aisle, collected his fares with hardly a smile.

The Pullman porter with his manner so fine, pickin’ up shoes just to give ‘em a shine.

Watching the scenery rolling on from an open obs or a Vista Dome,

You traveled relaxed and arrived the same, on a railroad passenger train.

Gone are the trains that we knew so well like the Golden Rocket and the Southern Belle,

The Texas Eagle and the Wolverine and the Panama Limited to New Orleans,

Pocahontas and the Banner Blue, Pioneer Zephyr and the Cannonball too.

Deep in memory we’ll cherish the fame and the glory and the grandeur of the passenger train.

Rutland Road

(Laurie Lewis: fiddle, vocal; Patrick Sauber: banjo; Tom Rozum: mandola)

A road with a checkered history and sad ending was the Rutland Railway, a line that ran from Bellows Falls and Bennington, VT to Ogdensburg, NY on Lake Ontario. The Green Mountain Flyer was its crack passenger train connecting Montreal with Boston. Surviving several owners, a failed attempt at developing a fast freight service with its Whippet trains and enduring harsh Vermont and Adirondack winters, came to naught as a strike by rail workers shuttered the railroad in 1961 before it was ultimately abandoned in 1963. This song chronicles the railway’s birth and struggle to survive, and mourns the death throes leading to its abandonment; an unbecoming fate for such an intriguing railroad.

What can I say about Laurie’s interpretation of the song? My wife and I both sat up and leaned into the speakers the first time we heard it. I love the feeling of Patty Loveless’ version of “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive.” Laurie’s soulful rendition of Rutland Road captures that same feeling of loneliness, impending doom, and sorrow at the loss of something dear. I never would have thought of this type of adaptation for this song but she’s hit the mark here. I can’t see this being sung any other way now. I’m going to have to learn how to do it this way myself.

The clouds are dark and gray. It is such a gloomy day.

And in the valley all is still. No trains will run today.

Back in eighty-three across the north country

There came a mighty engine’s roar headed for Ontario’s shore.

Across the mountains high and through the valleys wide

There runs a rough and rugged trail they call the Rutland Rail.

A gallant attempt but late, the Whippet was doomed to fate.

And the Green Mountain Flyer no more rolls on into Boston town.

September of sixty-one the Rutland’s life near done.

The strike call was a louder cry. The Rutland began to die.

All across Lake Champlain to Vermont and back again

The keys lay silent, the sounders still along the Rutland Rail.

The doors were closed and locked, the engines lay dead in the shop.

Mother Nature began to claim her trail known as the Rutland Rail.

The rails let out a cry as the torch cut through their side.

And the stations’ windows gazed with hollow stare

At the sights that they saw there.

Now the rumbling trains are gone. The stations stand forlorn.

Only memories remain of the bygone days along the Rutland Rail.

The clouds are dark and gray. It is such a gloomy day.

And in the valley all is still. No trains will run today.

No trains on the Rutland Rail. Gone is the Rutland Rail.

East Broad Top

(Scott Huffman: guitar, lead vocal; Tom Rozum: mandolin, vocal; Laurie Lewis: string bass, vocal; Bobby Black: resophonic guitar; Patrick Sauber: banjo)

Narrow gauge railroading was not limited to the west and a visit to the East Broad Top Railroad in central Pennsylvania took me back to the 1930s. Wandering around the original facilities in Orbisonia, I thought of what it might have been like to work on the railroad during one of the darkest economic times in our history.

The life of a worker in a coal mining operation is hard, to say the least, but during the Great Depression that hardship must have reached unheard of limits. This song speaks of that hardship but also the resilience and camaraderie of those who worked the railroads of this country during that difficult time. To emphasize that point, I enlivened the story by using the names of people who have played a significant part in my railroad life: Nelson Husted, the man who first taught me to run a steam locomotive at the Rail City Museum; Warren Tisler, who was a great Mid-Continent engineer to learn from, as were Tom O’Brien, Van McCullough and Jim Bertrand, who became good friends; and Mike Palmer, a NYO&W agent at Accord, NY, who shared memories and gifts from his life.

I cannot think of a more fitting tribute for these men.

I can only describe this song as a sleeper. I lost the written lyrics and was only able to contribute it to this collection by tracking down a version I recorded on a cassette tape recorder back in the 1980s. It was a song I never enjoyed playing because it seemed clunky and dragged. I intended it to be a slow, sad song about a hard time in our history. But the CD’s more upbeat rendition has turned this orphan into one of my favorites on the album. I always had a hard time with the chorus, having difficulty getting the best inflection for these lines, but Scott has done it perfectly. I guess Carolyn Hegeler’s initial reaction to it, as well as Laurie’s, was based on a better vision than mine. Thanks for turning this one around.

When I hear somebody say this world is crazy

It sets my mind to wanderin’ to a time so long ago.

It was in the Great Depression back in ‘37

When the thing that kept me goin’ was a railroad hauling coal.

In the Allegheny Mountains in the state of Pennsylvania

I lived in a rundown shack in the shadow of the mines,

Where I woke up in the mornin’ with the fire not far from dyin’

And the cold wind blowin’ through the cracks chilled the body and the mind.

East Broad Top, my family and friend.

East Broad Top, wish I could ride again.

East Broad Top, your lonesome whistle’s whine.

I rode your rails down the narrow trail into a better time.

There wasn’t much in wages, the hours were outrageous.

Sometimes it was many days ‘for we would turn a wheel.

But over in the roundhouse you could always thaw out

With a good hot cup of coffee ‘round the old potbellied stove.

Nelson ran the engine, Warren did the firing.

Tom and Van and Jim and Mike, they were all part of the crew.

We all helped one another with beans or bread or butter

And we all stuck together and somehow made it through.

East Broad Top, my family and friend.

East Broad Top, wish I could ride again.

East Broad Top, your lonesome whistle’s whine.

I rode your rails down the narrow trail into a better time.

We worked in the morning before the sun was dawning

Firin’ up the engines and makin’ up the trains.

Southbound we hauled empties. Northbound was coal for Pennsy.

The engine barkin’ loud, the drivers slippin’ in the rain.

I rode the rails in hard times, rode the rails in war time,

Rode the rails to victory and to the final peace.

But now the tracks are rusty, the engines cold and silent.

All that’s left are memories and ghosts that never speak.

East Broad Top, my family and friend.

East Broad Top, wish I could ride again.

East Broad Top, you made me what I am

You taught me love of simple things and you made me a man.

You taught me love of simple things and you made me a man.

The O&W Line

(Scott Huffman: guitar, vocal; Tom Rozum: mandolin, vocal; Patrick Sauber: banjo; Bobby Black: resophonic guitar; Laurie Lewis: string bass)

In a field near the hamlet of Northfield, north of Sidney, NY on the New York, Ontario & Western Railway, a Mother Hubbard locomotive, also called a Camelback because the locomotive cab was located halfway down the boiler, collided head-on with another train. These “cornfield meets” have been the subject of many stories and songs and so did this wreck inspire The O&W Line. The fireman on these locomotives would be at the back end shoveling coal so the engineer was alone in the cab, unable to see an approaching train around the curve. With a full load of passengers, the engineer in this song stood by his post, trying to slow the train to reduce the casualties on both sides. Alas, at the end, he knows his lot is to “stay and die here” on the O&W Line.

My head snapped when I first heard this track. These songs were written in a more traditional country style and a bluegrass rendition was never considered. But hearing this track, it is amazing to think this song was probably always meant to be done this way. The lyrical adaptations to fit the tempo work perfectly. I am a big banjo fan, having tried to teach myself the five-string banjo back in the 1960s in upstate New York (where no one played the banjo back then), and I love the banjo work on this and the other cuts. I also love the harmony, as I sing almost the identical harmony to myself when listening to the CD. Another favorite – wait, they’re all favorites.

I left old Sidney late one night four hours behind time

Headin’ down old Walton way on the O&W Line.

2-7-5 was doin’ fine, smoke was rollin’ free,

Then like a ghost a light appeared down the track in front of me.

I sat there for a moment, paralyzed by the sight.

I wished I’d seen it sooner, but the track curved to the right.

I turned ‘round to my fireman, but he was not in sight,

Firing the Mother Hubbard that we rode into the night.

I pulled the whistle cord and then hit the air

And midst all the noise I said a little prayer.

The lights kept coming towards us. I said that’s all this time.

This will be my last trip on the O&W Line.

I could hit the cinders. I might be safe that way,

But I’ve got to try and save all the people on that train.

So I’ll stay and die here, if that lot is mine.

I will give my all for the O&W Line.

I see her markers now and I hear the engine’s roar.

These will be the sights and sounds I’ll never see no more.

The steam shoots out around me. The steel, it bends and whines.

Yes, this is my last trip on the O&W Line.

The Ballad of Bill Strauss

(Scott Huffman: guitar, vocal; Tom Rozum: mandolin; Patrick Sauber: banjo; Chad Manning: fiddle; Laurie Lewis: string bass)

This song was inspired by one of my best friends, Paul Strauss, who believed his great-grandfather, Bill Strauss, was an engineer on the Illinois Central Railroad and was killed in a wreck. While it turned out that he was killed in a train wreck near Milstadt, IL on April 2, 1912, he actually worked on the Mobile & Ohio. We learned of this correction too late since the lyrics were already complete. And besides, M&O just doesn’t fit the rhyme. Written in the style of the “Wreck of the Old 97” in glorifying the brave engineer who was the victim of circumstance, the Ballad of Bill Strauss was my first attempt at writing a railroad song.

When the intro to this song came on, I thought “Why are they playing ‘The Wreck of the Old 97?’” I loved Flatt & Scruggs’ version of that song and this version of Bill Strauss fills me with the same excitement. I put a lot of high notes in the melody but the absence of some doesn’t detract at all. In fact it seems like a lot of thought went into this arrangement and it came out great.

It was in the afternoon on a sunny day in June

Down at the old roundhouse.

Oiling up 123 of the old IC

Was that brave engineer, Bill Strauss.

He pulled out a string of freight about 4:08.

One twenty-three was really doin’ fine.

He highballed it through because he knew

That the track crew had just fixed the line.

He was goin’ round a curve when he felt the engine swerve

And what he saw filled his heart with dread.

And he whispered a prayer as he drew on the air

And soon old Bill was dead.

Everyone at the scene saw the battered machine

And wondered what Bill saw ahead.

When the gang crew came back they looked at the track

And saw that the rails had spread.

Now you all listen well to the story I tell

Of a life that’s gay and free.

Just be sure of your load, keep your eye on the road

When you’re hoggin’ on the old IC.

Four Ribbons of Light

(Scott Huffman: guitar, vocal; Bobby Black: resophonic guitar; Chad Manning: fiddle; Tom Rozum: mandolin; Andrew Conklin: string bass)

During my high school years, my best friends John Tomandl and Paul Strauss and I would spend evenings on the New York Central double track main line around Weedsport, NY. Lots of freight and passenger trains would roll by and we would stay until late at night, watching the headlights and marker lights cut through the dark. John noted how the moonlight on the rails looked like four ribbons of light. Combining that imagery with a traditional railroad theme of a railroader reaching the end of life, the thought of taking that one last ride was the inspiration for this song. It is an attempt to convey an old railroader’s consolation that he would one day soon be reunited with friends long gone to that great railroad in the sky. It was therefore important to me that this song be the final selection on the CD.

As I went out a walkin’ one late night in the fall

I went down by the station, Lord, and heard a mournful call.

The moonlight shown on the railhead, four ribbons of light in the night.

I looked up to the north and saw a strange ghostly light.

I heard the bell a-ringing. I heard the whistle whine.

And the sight of smoke a-blowin’, Lord, sent chills right down my spine.

The pounding of the drivers was like the thunder from the skies.

And the bright glow of the headlight was blinding to my eyes.

The whistle screamed its warning as toward me it did fly,

The rockin’, rollin’ ghost train on its midnight ride.

The engineer at the throttle was in the wreck of ‘93

And I swear that fireman shoveling coal looked like my daddy to me.

As the train roared by me in the coaches’ dim, yellow light

I saw the faces of many a friend I had in days gone by.

When the train rolled by me and faded out of sight

A voice cried, “You’ll be ridin’ soon like we have on this night.”

Standing there at trackside I watched the markers’ glow.

I knew that I would be at peace when on that train I go.

Four ribbons of light in the moonlight. Four ribbons of light in the night.

And that ghost train takin’ this railroad man, takin’ me home tonight.

And that ghost train takin’ this railroad man, takin’ me home tonight.

About the Album

Dear Laurie:

I am ecstatic with what you and your fellow artists have done with this project. I am humbled to think you thought enough of my work to devote so much time and creative effort to this project. My wife and I were mesmerized listening to it – the first time, second time, third time – it sounds better with every listening. You have more than done justice to the messages I intended to evoke with the music. You have taken my meager efforts and propelled them beyond my imagination.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Ken

Steam and Steel: Songs of Railroad’s Golden Age

All songs written by Ken Hojnacki except “The Wreck of No. 9” by Carson Robison.

Produced and arranged by Laurie Lewis

Recorded at LewieToons, Berkeley, CA by Laurie Lewis

Mixed at the Rec Room, Nashville, TN by Ben Surratt and Laurie Lewis

Mixing Engineer: Ben Surratt

Mastered by Ken Lee at Ken Lee Mastering, Oakland, CA

Project Coordinator: Carolyn Hegeler

Executive Producer: Don Meyer

Album art: Genevieve Davis

Album design: David Miller

Railroad Glossary

Railroaders have a language all their own and a lot doesn’t make sense to those outside the brotherhood. Herewith, a glossary to help explain some of the more obscure references in the songs.

Baldwin — The Baldwin Locomotive Works was located outside of Philadelphia, PA and was one of the largest locomotive builders in the world. Alas, when steam locomotives gave way to diesels, Baldwin was not able to make a successful transition.

Narrow gauge — Nearly all railroads in operation in the United States are standard gauge — 4’ 8 1⁄2 inches between the inside of the railhead. In the last half of the 1800s, narrower gauges were used to reduce the cost of construction and equipment. Three foot gauge was the most popular and the Denver & Rio Grande in Colorado had the most extensive system. However, the East Broad Top in Pennsylvania was also built to three foot gauge.

Parlor Car — To attract wealthier patrons, in the late 1800s, railroads began purchasing specialty passenger cars designed to provide more amenities for an additional cost, much like first class airline seats today. Instead of rows of bench seats as in the typical coach, a parlor car had individual wicker or leather chairs, often swiveling or free to be moved about the car so passengers could feel like they were in their living room. Because of the greatly reduced number of seats in parlor cars, the additional cost of riding in these cars meant most never experienced this luxury.

Pullman porter — The largest manufacturer and operator of railroad sleeping cars was the Pullman Company. Each car had an African American porter to assist passengers with their luggage and other needs. Passengers in private rooms could open a small compartment where they could deposit their shoes. The porter would pick up the shoes after everyone was asleep and return them with a high polished shine.

Obs — This is slang for “observation car,” another specialty type of car that might be a sleeping, lounge or parlor car but with a larger, open platform on the back where passengers could sit in folding chairs and enjoy the open air and scenery falling away from the train as it rolled along. This was also an extra fare car in nearly all cases.

Vista Dome — The Budd Company, a pioneer in building stainless steel streamlined cars, built the first car with a glass dome on the center of the roof where passengers could get a panoramic view of the scenery.

The Whippet — In 1939, the Rutland Railroad was in deep financial difficulty, as were many railroads during the Great Depression. A plan was devised for a fast freight service from Boston to numerous destinations across the US in conjunction with other railroads. Unfortunately, competing routes provided faster service and the Whippet failed to erase the red ink from the Rutland’s ledgers.

Keys and sounders — Before telephonic communication, the telegraph was the means of transmitting messages between towns. The railroad depot usually had a railroad company line and the Western Union line for news and business messages. The key was the device used by the sending operator to create the dots and dashes of the Morse Code message. The sounder was the listening device where a brass bar was magnetically moved to “click” against another metal bar so the receiving operator could decipher the message. Railroads made extensive use of telegraph to regulate train movements over their routes.

Drivers — On a steam locomotive, steam pressure moved large pistons which were connected to siderods that turned large drive wheels to put the locomotive and train into motion.

Mother Hubbard, Camelback — As noted in O&W Line, many Eastern railroads used locomotives with the engine cab astride the boiler instead of at the end in order to burn anthracite coal, which required a bigger firebed. These engines had many nicknames such as Camelbacks, from Baltimore & Ohio’s original 1853 Ross Winan’s Camel locomotive and Mother Hubbard for the cab’s resemblance to that lady’s cupboard in the children’s rhyme. On the Ontario & Western, the “double cabs” outnumber conventional cab locomotives over the history of the railroad. Because the fireman could not ride in the cab and fire the locomotive at the same time, the engineer was often alone. The long boiler ahead of the cab obstructed the limited view of the engineer and even if a brakeman was riding on the other side, the boiler itself impaired any communication across the top of the boiler. New construction of this type of locomotive was banned by the government in 1927 but older models were used until the 1950s.

Hit the air — Trains are stopped by use of airbrakes on the cars and locomotive. To hit the air means apply the brakes, usually in an emergency application.

Hit the cinders — Many railroads used cinders from the locomotives for ballasting their track instead of rock. When the crew had to get off equipment quickly in an emergency, they would jump to the track bed, literally hitting the cinders.

Markers — Special lamps with three or four lenses. In proper definition, marker lights are used on the end of the train, with red showing to the rear and green or amber showing to the sides. As used in the song, the “markers” are more properly classification lamps to indicate the train is an extra train not on the timetable or is one section of a regularly scheduled train.

Highball — A signal from the brakeman or conductor to the engine crew that they had permission to proceed. The term comes from an early wayside signal consisting of a large ball with a rope through the center which was hoisted to the top of a pole to indicate the train could proceed; literally, a high ball.

Gang — Track gangs were crews assigned to maintain the tracks on a certain section of the railroad. They would change rails, replace ties and perform any regular maintenance needed.

Rail spread — Rails are kept in gauge by spikes driven into the ties on each side of the rail base. Rotted ties, missing or loose spikes or drastic changes in temperature can cause the rails to loosen and when a locomotive or car rolls over the spot, the weight and moving forces can push the rail outward, spreading out the distance between the rails and derailing the train.

Hoggin’ — A locomotive was sometimes referred to as a “hog” and an engineer as a “hogger.” Hence, hogging would be running a locomotive.

IC — The Illinois Central Railroad which ran south from Chicago to New Orleans.