Ramsey's Car Truck Shifting Apparatus

As railroad technology improved and railroads multiplied and grew longer, railroad builders began to debate which gauge was “best.” Narrower gauges seemed to have a better ratio between the weight of a car (“tare weight”) and the load it could carry, while wider gauges could carry bigger cars, and offered better stability and speed. But since the technology of the day didn’t support really big cars or really high speeds, the choice of gauge was still more a matter of theory than of practice. By the time of the Civil War, however, railroads had multiplied, grown longer and begun to interconnect to the point that the adoption of a single gauge was becoming important. And with passage of the Pacific Railway Bill of 1862, which provided that the first transcontinental railroad be built to the gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches [56½ inches], that gauge was all but officially adopted as “standard.” Yet the subject of which gauge was “best” really hadn't yet been settled as

far as civil engineers were concerned. During the 1860s, a great debate on the

subject was set off when Andrew Francis Fairlie (1831-1885), a British engineer, advocated

strongly for “narrow gauge” [anything less than 4 feet 8½ inches and

hereafter abbreviated n.g.]. Fairlie was first and foremost a locomotive

designer/builder, and his advocacy was based on his experience with the Festiniog Railway in north Wales, a railroad for which he had designed a

special type of locomotive. One of these ideas was that n.g. railroads were cheaper to build, especially where the terrain was rugged. He believed a locomotive of a given size could pull the smaller n.g. cars up steeper grades and around tighter curves, thereby greatly lessening the initial cost of building the kind of straight and level track we now think of as a modern railroad. It was, in fact, this lessening of initial cost that was probably the greatest single factor spurring the n.g. boom of the 1870s and 1880s. Another factor spurring the boom was probably the stock market collapse of 1873, which initiated a depression that made money for railroad expansion virtually unavailable for several years, and tough to get at reasonable rates for several more. With the demand for railroad transportation unabated, an “inexpensive” n.g. line often became the answer to promoters’ dreams. In the United States, this gauge-debate is best represented by the 1875 publication of Howard Fleming’s book Narrow Gauge Railways in America. Fleming was either a “prominent civil engineer” [Hardy] or a “Philadelphia railroad supply dealer” [White]. (He could conceivably been both.) His book reflected the experience of n.g. railroads built in the United States since 1870, a good many of which had been built by the time it was published. Foremost of these was the Denver & Rio Grande in the mountains of Colorado, built to a gauge of 3 feet. By 1879, there were 148 n.g. railroads in the United States, operating over 4,188 miles of trackage. This mileage grew by 1,000 miles during the next year. By 1886, at the height of the n.g. boom, there were 210 railroads operating over 12,116 miles of trackage. {242} The primary problem of the narrow gauge railroads was “interchange,” what we now think of as simply switching a loaded car from one railroad to another to complete its journey from shipper to receiver. This simple switching of cars wasn’t possible where the gauge of the car was different from the track gauge of the receiving railroad. It was necessary to unload the cargo and reload it onto a car of the railroad of the other gauge (what is known in the industry as “breaking bulk”). Breaking bulk was an operation that not only took time, but one that increased costs and subjected the load to possible breakage and pilferage. At some point, someone had the idea of simply lifting the loaded car off its trucks—the four-wheeled assemblies (known as “bogies” by those across the pond)—and lowering it back onto trucks of the different gauge. This is made possible by the nature of the connection, which is in the form of a shaft known as a king-bolt or center-pin protruding down from the body of the car through the center of the truck assembly. And this is where Robert Henry Ramsey comes into the picture. He did not conceive the idea of switching trucks, but he certainly had one of the most widely used methods of doing so.

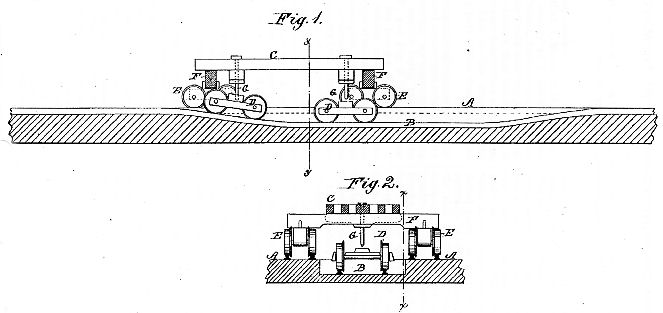

In 1876, Ramsey obtained a patent for a totally unique method. Most transfer devices lifted the unmoving car body from its trucks and then lowered it onto trucks of a different gauge using some sort of suspension device such as a block and tackle. Ramsey’s method was quite different. Ramsey’s “apparatus” consisted of three parallel tracks, the center of which ran down into a depression several car-lengths long, then ran up again level to the others. The center track entered the depression at one gauge, then exited at the other. Two sets of “shifting trucks” ran on the outside tracks. To operate Ramsey’s apparatus, a car was positioned on the center track, short of the depression. A set of shifting trucks was brought alongside at one end of the car, one on each side. A beam was run across under the car and each end positioned on top of a shifting truck. This was repeated at the other end of the car with another beam and set of shifting trucks. The car and its two sets of shifting trucks was then drawn toward the depressed track. As the car began to descend, its body came to rest on the beams between the shifting trucks. As it moved further along, its trucks descended into the depression until they had slid entirely off the king-pins. As the car, supported by the shifting trucks, moved toward the far end of the depression, trucks of the new gauge were positioned beneath the king-pins and moved along so as to be rise up onto the king-pins. As the car reached the far end of the depression where the tracks were again level, it was fully seated on the new trucks and the body rose up off the supporting beams, which were then removed.

Ramsey must have been intrigued with the idea of car body transfer, as he obtained at least three more patents for different types of devices for that purpose, the latest in 1884. Truck shifting sounds eminently workable, doesn’t it? Well, it did work. . . after a fashion. Narrow gauge cars, being narrower and lighter, generally rode well on standard gauge trucks. But because they were built to pull other, lighter, narrow gauge cars, they were often too weak to place in the middle of a train, and thus had to have special handling, requiring additional time and labor. And this raised costs. Standard gauge cars, being larger and heavier, seldom rode well on narrow gauge trucks. The greater width increased overhang, challenging clearances. Greater width and a higher center of gravity also made them unstable. (Think of a fat woman in high-heeled shoes.) This instability, coupled with the greater weight, required special handling and slower running, and both of these raised costs. On top of that, the whole shifting process took time, employed additional labor and required an investment in the apparatus and in additional sets of trucks. Impractical and uneconomic as it sounds, some railroads did it to the very end. The East Broad Top, a coal road in Pennsylvania did it in its Mt. Union Yard right up to the railroad’s abandonment in 1956. For More Information —

Fleming, Howard. Narrow Gauge Railways in America. Philadelphia, PA: Press of the Inquirer P. & P. Co., 1876.

White, John H. “The Narrow Gauge Fallacy.” Railroad History No. 141, Autumn 1979. Railroad & Locomotive Historical Society, Inc. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||